The men who stare at trees

How to get our nature fix

Happy Friday!

This morning I spent 60 seconds staring up into a tree.

On a circuit of the local park, I broke off my run to stand and stare at bark branches twigs sky.

I felt looks from dog walkers.

The first time I attempted this task, I checked my watch at barely 40 seconds.

40 seconds.

My untrained unfocussed attention span is two thirds of a minute. I can hardly blame that entirely on shiny screens, but the interior life dictated by the screen is suspect number one.

And it doesn’t feel great to be holding my breath.

I stared up for another 20 seconds, laughed at the lichen and continued my run with a light heart and a smile.

The Nature Fix

Why might staring up into a tree for a minute have made me feel lighter? One answer might be in the fractal patterns of the bark branches twigs sky, especially noticeable in winter.

What is a fractal? Essentially, a fractal is an image that exhibits similar, repeating patterns, whether you’re observing from far away or super close up.

Instead of going deeper into abstract mathematical definitions, I’ll let this Wikipedia image of zooming into a fractal Mandelbrot set do the work:

It’s like how branches branch off into smaller branches and smaller branches branch off into twigs and twigs into leaves and leaves into leaflets and leaflets into veins and the whole set is mirrored underground in the roots.

Anyway. It turns out that a specific range of fractals are good for us.

In one of a series of remarkable studies, physicist Richard Taylor and psychologist Caroline Hägerhäll found that viewing images with a fractal dimension of between 1.3 and 1.5 easily led people into the alpha brain state (‘wakefully relaxed’) associated with increased creativity and reduced depression.

Nature adores these low- to mid-range fractal dimensions and they are found everywhere, from the patterns we see in snowflakes, coastlines and clouds to the structure of our lungs and neurons and even the movement of our eye’s retina.

This is an important discovery: our eyes work over an image in the same fractal patterns of which natural landscapes are composed. In nature, then, our visual cortex feels most at home: confident, comfortable and, assuming no tigers are detected, wakefully relaxed.

Such ‘visual fluency’ is stress-reducing in the same way that ‘French fluency’ is stress-reducing when you step off the ferry in Calais.

This is not, when you think about it, a surprise. Our eyes evolved to seek food and spot danger in natural landscapes, after all.

What’s mind-blowing is that scientists have studied and uncovered this and can point to our city streets and say things like: ‘The fractal dimensions are totally wrong here. You’re going to feel stressed’, or: ‘Looking up at those trees gives your visual cortex a fractal dimension of 1.37. You’ll feel wakefully relaxed.’

And doesn’t this computer-generated fractal pattern look like the outline of a winter’s tree against the sky, or a lichen’s tattoo on bark?

(It’s actually an aeriel photograph of a river basin in Siberia. Tricked ya!)

The Nature Fix

When I got in from my tree staring, I went online and bought a hammock as a promise to my future self to spend more time among the branches. I know that I want to spend more time outside, but I struggle to make it happen.

I’m not alone in this.

Humans are terrible at forecasting how great we’ll feel if we only get outside.

When psychologist Elizabeth K Nisbet of Trent University sent 150 students out for a walk, she found that they consistently overestimated how much they’d enjoy exploring underground tunnels and consistently underestimated how great they’d feel strolling along a canal towpath.

Clearly gutted, Nisbet concludes that:

People may avoid nearby nature because a chronic disconnection from nature causes them to underestimate its hedonic benefits.

It’s hard to prioritise the great outdoors when we persistently fail to draw a line of connection between going outside and feeling good. Would you keep going back to a doctor who you thought was a quack?

Somehow, we need to force ourselves outdoors and trust that nature will do its work whether we credit it or not. It’s not easy, in fact you might call it a challenge…

The 30x30 Nature Challenge

The David Suzuki Foundation run an annual challenge in which participants try to spend 30 minutes in nature every day for 30 days. That might not sound like much, but I for one don’t hit those kind of numbers, especially not in winter.

Since 2013, the Foundation have added science to their 30x30 nature challenge and have tested what happens to our wellbeing when we make a regular commitment to more outdoors.

In 2017, the same Elizabeth K Nisbet we met earlier published the results of the 2015 challenge. They make for fascinating reading.

The first thing to note is that, even before the challenge, the 1,896 participants were already getting their 30 minutes a day on average. But that wasn’t not the point. The point was to make a commitment to getting outside every day for 30 minutes - not just on average.

That commitment saw total time spent in nature double over the course of the challenge - an extra 8 hours per week.

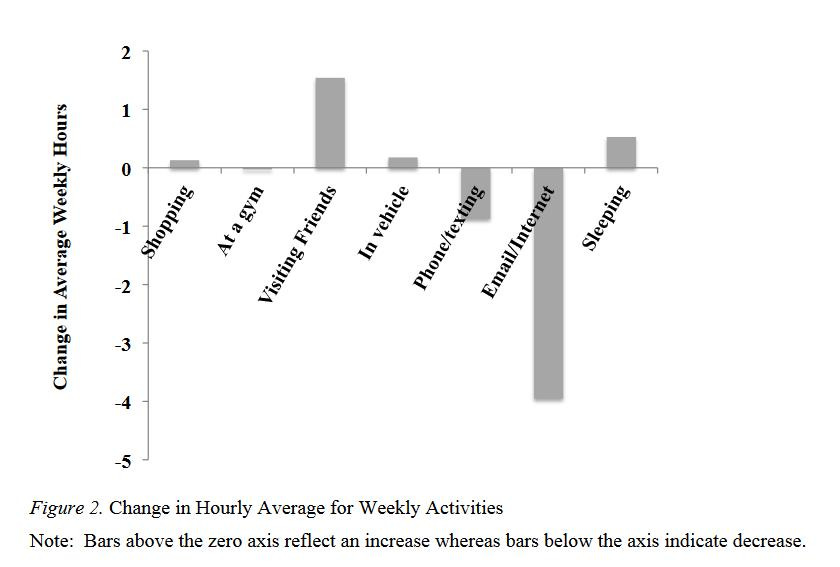

Of course, those 8 hours have to come from somewhere and, on average, participants in the study spent 52 minutes less per week on their phones and a ridiculous 3 hours 57 minutes less time on the Internet.

None of the other measured categories of time use - shopping, at the gym, in vehicle, and sleeping - saw statistically significant increases or decreases.

Except one: visiting friends.

The challenge participants spent, on average, an extra 92 minutes with friends every week. That’s a huge increase. Apparently, humans love to share nature.

We haven’t even got to the proper results yet, but you can see where this is going, can’t you? Surely any activity that means less screen time and more friend time is going to be good for our sense of wellbeing, isn’t it?

Yes.

Positive affect (being content, enthusiastic, relaxed, joyous) went up over the course of the study. Negative affect (being anxious, sad, irritated, hostile) went down. Fascination (awe, fascination, curiosity) went up. Vitality (feeling alive and vital, having energy and spirit) went up. All results passed the test for significance (p<0.001, stats fans).

Topper: the more participants increased their time in nature, the stronger were the positive effects on their wellbeing. Good news for those of us who struggle to get outside: we’ll feel the most benefit.

An awesome minute

I got the idea for my minute of tree-gazing from a 2015 study that used a grove of 200-foot tall Tasmanian eucalyptus trees to inspire awe.

Awe is an experience that reminds us of our puny position in the universe. Awe subsumes us into the whole and can help us forget our struggles, strife and stress for a moment. It’s mindfulness, only much more fun.

Paul Piff, psychologist at the University of California, has also found that nature is really good at delivering awe and that humans can convert awe into prosocial behaviour.

Staring up at those eucalyptus trees made the study participants more helpful to a clumsy experiment stoodge who dropped all his pens than did participants who stared up at a building. They also reported feeling more ethical and less entitled. Rather than focussing on themselves, the tree-starers opened up and orientated more towards others.

Now, my stubby Bristolian park is no grove of mighty eucalyptus, but as I finished my run, I decided to try my tree-gazing minute again.

This time I didn’t check my watch until more than 90 seconds had passed.

Nature fixed.

From Biophilia and the fractal geometry of nature, Caroline Hägerhäll

Ideas for a nature fix

Stand at the foot of a tree and stare upwards for a minute.

Get fractal and gaze into a fire (or a Jackson Pollock painting).

Do a sit spot in nature. Go to a favourite place and, um, sit there. Go back tomorrow. Nature Mentor has a great introduction to sit spotting, but it’s really no more complicated than sitting and spotting.

Climb a tree and find a comfy branch.

Watch the ripples of rainfall onto a river, lake, canal or - in extremis - a puddle. Alternatively, follow the traces of droplets down your window pane.

Hypnotise yourself with waves wherever you find them.

Look up at the cloudscape.

On a sunny day, watch the shifting shadows cast on the ground by the wind and the trees.

Watch a lightning storm.

Inspect the weeds between cracks in the pavement or the lichen on a wall.

If you really want to get sciency, commit to being out in nature for 30 minutes a day, every day, for 30 days. I’m on Day 1!

~

99 percent of the research for this post came from the excellent book The Nature Fix by Florence Williams.

Your neck of the woods?

I’m still in Bristol, but over the weekend I’m taking trips out to Penarth and Clevedon, facing each other across the Bristol Channel.

One thing that I won’t be doing on Sunday is watching the men’s Australian Open tennis final between Dominic Thiem and Novak Djokovic. The tournament has made me, once again, marvel at the serene agelessness of 32-year-old Djokovic and his seniors Rafa Nadal (quarter-final, 33) and Roger Federer (semi-final, 38).

I enjoyed perusing this Wikipedia table, which compares their career evolution by age. If Djokovic wins on Sunday - and he is the strong favourite - then the three greatest 32-year-old tennis players of all time will be tied on 17 Grand Slams each. (Such a confusing sentence to write…)

Djokovic has never been the ‘age leader in completed years’, but surely he will overtake his peers before he retires, aged 57.

Much love,

dc:

CREDITS

David Charles wrote this newsletter. He publishes another newsletter about reading called Books Make Books. David is co-writer of BBC Radio Wales sitcom Foiled, and writes for The Bike Project, Forests News, Global Landscape Forum, Elevate and Thighs of Steel. He also edits books about adventure, activism and more. Reply to this email, or delve into the archive on davidcharles.info. Thank you for subscribing!

Thanks to DRL for sharing this image and inspiring this newsletter.