Pinenes [🇩🇨]

This week: the healing power of pines and the smell of kimchi, plus dictionaries, donors and dream trains...

Happy Friday!

And welcome to a break in the weather — the trees are exhaling. Before we get cracking, thanks for all your comments on last week’s questions. It reminded me that six years ago I invented (?) the Questionable Meeting, in which participants may only speak in the interrogative mood.

I feel strongly that, in a culture that seems to value certainty above all, a great intellectual advantage could be gained by spending more time asking instead of answering questions, using them alone as a form of unrequited dialectic, to reach beyond the ego-driven drivel of rapid response.

[🇩🇨] Introducing questionable meetings: the original 2014 description of the meeting format, now online

[🇩🇨] The trees knees: today’s long read, a walk in the gardens of Bournemouth — once desolate heath — now home to famous sequoias, cedars and cypresses

Above: Did you know that trees can grow knees? A Bald Cypress in sunshine, Central Gardens, Bournemouth

The trees knees

I grew up in a swathe through beech forests so it’s no wonder that I find the pines, redwoods, sequoias, cedars and cypresses of the south coast alluring.

Today, Bournemouth is famed for its vigorous tree culture — famous enough in 1948 for poet laureate John Betjeman to take the piss out of the modernising town clerk who longs to build blocks of flats over the town’s clifftop pine woods:

I walk the asphalt paths of Branksome Chine

In resin-scented air like strong Greek wine

And dream of cliffs of flats along those heights,

Floodlit at night with green electric lights.

My view from the eighth floor of one of those ‘cliffs of flats’ is dominated by city and canopy, a testament to a centuries-old commitment to greening and salubrious landscaped woodland.

But it could all have been so different.

From heath to health

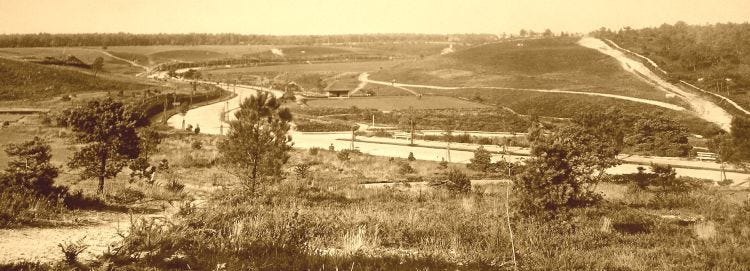

Above: Meyrick Park, Bournemouth, ~1897 (from The Pines of Bournemouth)

Two hundred years ago, Bournemouth was at the arse-end of what Thomas Hardy imagined as ‘the Great Heath’ and described as follows in Return of the Native:

A place perfectly accordant with man’s nature – neither ghastly, hateful, nor ugly; neither common-place, unmeaning, nor tame; but, like man, slighted and enduring; and withal singularly colossal and mysterious in its swarthy monotony!

Other critics were less kind. The History of Bournemouth: 1810-1910 portrays the area in the years before habitation thus:

At that time, stretching right away from Christchurch to Poole was a vast, desolate heath, covering an area of probably twenty square miles.

Meanwhile, at some point before 1875, a contemporary writer nailed Boscombe as ‘a scene of indescribable desolation’.

The turning point for the blasted land came in 1809, when, out of nowhere, a pub appeared. Where there is booze, retired army officers shall not be far behind and Lewis Tregonwell and family became the first official residents of the budding hamlet in 1812.

Latching on to far-fetched rumours that ‘pine-scented air’ was beneficial for popular nineteenth century maladies like tuberculosis, Tregonwell and Sir George Ivison Tapps, the owner of the pub, conspired to cover the heath with hundreds of pine trees, all the way down to the seashore.

Over the ensuing decades, these two wily entrepreneurs somehow transformed Hardy’s inhospitable heath into a miracle pine health spa.

Above: Invalids' walk, Bournemouth ~1895-1905 (Wikipedia)

But what’s almost more remarkable about this story is that those rumours about the health properties of pine were bang on the money.

Pine trees vs cancer

The scent of pine trees comes from its resin and specifically from two isomers of pinene. If you’ve ever used turpentine: it’s the same chemicals and the same woody smell. (Enjoy responsibly.)

Pinenes are a type of chemical called phytoncides. You might recognise the -cide ending there. Yep: pinenes kill stuff. It’s the pine tree’s all-natural antimicrobial killer defence spray.

And it works on us too.

Qing Li, an immunologist at Nippon Medical School in Tokyo, has been investigating the effects of phytoncides on the human body since the early 2000s.

In one, frankly astonishing, 2009 study, Li invited 12 men to come and stay with him for three nights at an ‘urban’ hotel. If that sounds dodgy, wait until you hear what happened next: every night, he pumped vapour from the pinene-rich oil of Hinoki cypress trees into their bedrooms.

At the end of the study, the poor men showed a significant increase in the activity of their natural killer immune cells (this is good: these cells kill cancer) and a significant reduction in noradrenalin (AKA norepinephrine), which usually increases when we’re stressed or in immediate danger.

They also reported feeling less fatigued compared to a control hotel stay that lacked the vapourous phytoncide air.

And so back to Bournemouth, where the tradition of ‘taking the tree air’ continues with the council’s healthsome Tree Trail. (Betjeman’s town clerk was fired, I hope.)

Untold riches — of Redwoods, Cedars and Cypresses

The trail is heralded as ‘a two hour circular walk through Lower, Central and Upper Gardens’, but so far I’ve spent over four hours and have only rather shakily identified half of the 14 mapped trees.

I could spend two hours alone at the foot of Bournemouth’s Dawn Redwoods, a species once believed to be extinct, forgotten for five million years, rediscovered in its native China during the Second World War, and now lording it over the social distancing picnickers and parkour traceurs of the Upper Gardens.

Or I could cosy up for an afternoon with the Blue Atlas Cedars, re-seeded from the mountains of North Africa and now almost shyly gathering around the Hedgehog Kiosk, as if waiting to be invited for ices.

I must find time enough too, far from their Mississippi swamplands, for the Bald Cypress, those of the tree knees, whose canopy has that fibrous quality of ferns writ large, leaves that are hardly there, yet diffuse the sun into soothing colour.

And this walk of almost infinite discovery scoots over the single greenway of Bournemouth’s central gardens. The verdant chines — of which Betjeman’s Branksome is but one — are a tree trail tale for another day.

Above: Alum Chine. A. R. Quinton postcard circa 1910 (Winston Churchill, RLS, and the Literary Chines of Bournemouth by David A. Laws)

~

Thanks to A.T. for discovering and then sharing the Bournemouth Tree Trail with me!

Can’t even…

These three little things have helped put the brakes on the Sisyphean boulder this week.

1. Reading on the toilet

I’ve never been one for reading while on the toilet. It’s always seemed vaguely unsanitary. But 10 days ago, for some equally vague reason involving Marcel Proust, I broke with a disgust of a lifetime. Using maths, I’ve worked out that, at a rate of 8 pages a day, that’s an extra 10 books a year I’m reading!

2. Sniffing kimchi

After two weeks of fermentation, my kimchi still isn’t quite ready, but it smells divine. I can hardly believe that the BBC recipe said that it would be good to eat after one night. That’s not kimchi; that’s salty cabbage.

3. Finishing Proust (abridged)

This week I heard the, expertly convoluted, final sentence of In Search of Lost Time: read, abridged and even partially translated by Neville Jason. It’s a wonderful listen — and, when I’m a millionaire (but after I’ve solved world peace), I’ll buy the unabridged 153 hour version.

So, if I were granted sufficient time to finish my work, I would not fail to describe men in it, even at the cost of making them seem like monstrous beings, as occupying so considerable a place compared with one so confined, which is reserved for them in space, a place which, on the contrary, is prolonged without measure since they are able to touch simultaneously, like giants plunged into the years, distant epochs through which they have lived, between which so many days have come to range themselves, in time.

Full marks to…

1. Ness Labs, James Somers, John McPhee and, above all, the lexicographer Noah Webster

It’s vanishingly rare that a single blog post changes the way that I write, but James Somers’s 2014 piece You’re probably using the wrong dictionary has done exactly that. If you ever use words, you would be doing yourself a lifetime’s favour to read this article.

If you suspect exaggeration, quickly peruse this definition of the word ‘news’. Any dictionary that quotes Milton to pin down such a mundane word is good in my book.

Thanks to Ness Labs for passing this link along the chain.

2. Firefox keywords

Continuing the dictionary-related geekery… If you use the Firefox browser, save the following bookmark:

https://www.websters1913.com/words/%s And assign to it a simple keyword — ‘w’ for example.

Now you can use the 1913 Websters to look up any word, say ‘remarkable’, simply by typing into your address bar:

w remarkableThere is nothing left remarkable

Beneath the visiting moon

William Shakespeare, Anthony and Cleopatra

Other browsers may vary. If you really want to get fancy, you could probably work out a way to add this search to the context menu (hard), or assign a shortcut that automatically opens a new tab with the 1913 Websters pre-loaded (easy).

3. All you donors to Around the World in 40 Days

After 14 days, we’ve cycled over two-thirds of the way around the world and raised over £57,000 for Help Refugees. In Athens this week, Khora celebrated the 6-month anniversary of moving into their new community kitchen by making falafel — for 900 people! This is the kind of delicious work that everyone’s helping to fund. Thank you.

Any more for any more?

It’s rare that we reach truly significant decision points. Maybe only a dozen in a lifetime.

When you dream of trains, it is only ever in order to miss them. We know this. So the next time you see one chuffing into view, turn away. Stay on the platform. You don’t need their bullshit.

Sometimes you need to get out of it to remember what you get out of it.

Bake your rotis on a medium-low heat. Too high and they become brittle.

Much love,

dc:

CREDITS

David Charles wrote this newsletter. He publishes another newsletter about reading called Books Make Books. David is co-writer of BBC Radio Wales sitcom Foiled, and writes for The Bike Project, Forests News, Global Landscape Forum, Elevate and Thighs of Steel. He also edits books about adventure, activism and more. Reply to this email, or delve into the archive on davidcharles.info. Thank you for reading!

Unlock the commons for £30

These free weekly newsletters are currently 1.6 percent funded. You can unlock the commons for everyone by becoming a paying subscriber for £30 a year. Thank you.