Persistence [🇩🇨]

This week: love and air, hedgehogs and foxes, and persistence...

Happy Friday!

And welcome to another glorious day—or I hope it is, wherever you are. I just spoke to someone in lockdown in Jakarta, but this week I’ve written something completely un-Covid. Scroll down for the story, or read online here:

It’s the curse of the most profound realisations that they’re doomed to rot as cliches, mined for the hit parade. Never mind. It still works for me.

Love is all around me

And so the feeling grows

It’s written on the wind

It’s everywhere I go

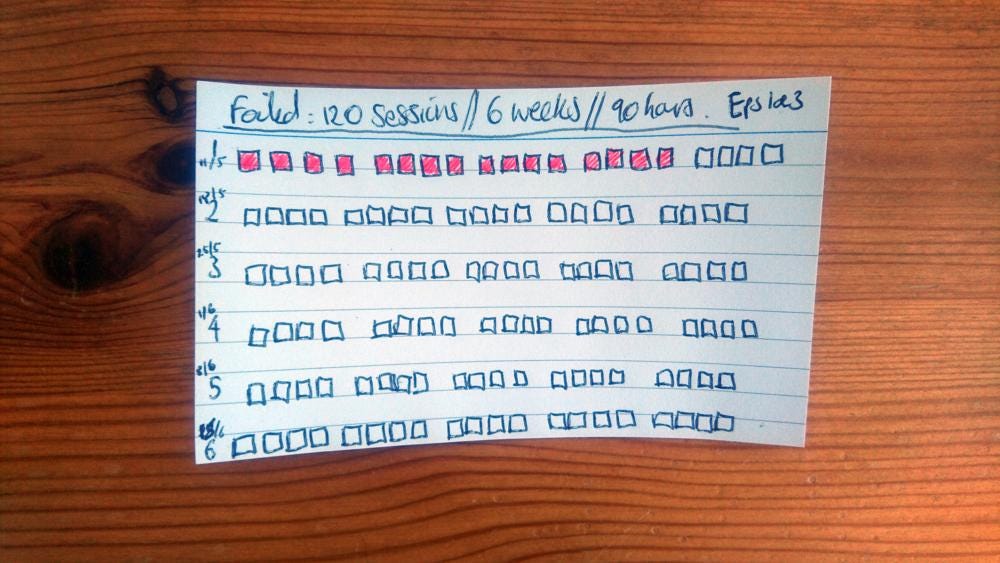

Above: Each one of those boxes represents 45 minutes’ work. By the time this card is filled in, Foiled Series 4 will be finished. Insha’allah.

Love is nothing special

Sometimes I forget to breathe. I’ll notice that I haven’t taken a deep breath in the last hour (or week) and, standing by the sink in the kitchen or staring into the pixels of my computer screen, I’ll consciously make the effort.

I’ve spoken to plenty of people who feel the same: we’re shallow breathers. But given how wonderful that first deep breath feels, wouldn’t we love to breathe a little deeper all the time?

After all, the air is right there, waiting for us to swallow it down to the bottom of our lungs. There are deep, inexhaustible breathfuls of air all around us, all the time. And breathing can do wonderful things.

Air doesn’t care whether we clear landmines for a living or make bullets for child soldiers in the Central African Republic. No matter: air is there for us.

Air gives us breath in abundance: we take as much as we please, almost without noticing. And, on the exhale, we pump out that sweet, sweet carbon the trees thrive on.

Breath in, breath out: the atmosphere is kept in balance. It is the base unit of our existence—and the existence of every living being on the planet. Air must be circulated. Without circulation, the whole system breaks down.

This is exactly like love.

Love is nothing special. Love isn’t something that we have to mine from the sweat of our brow. Love isn’t something tangible like fruit or clothing. It’s not even something purely conceptual like war or money.

It’s like the air: almost ludicrously abundant, the fundamental currency of life. Intangible, but real; everywhere, but invisible.

We might not be able to see the air, but we can all feel it: the rustle of the wind in the trees or the almost imperceptible caress of a zephyr on our cheek. At other times, the air is master of our existence: trapped inside a hurricane or in a storm on the high seas.

So too love: if we stop we can usually feel love even on the calmest of days. But love is no less there even when we can’t perceive it, in the same way that the air is no less there because we can’t feel the wind or see the trees swaying.

We don’t need to notice or think about the air in order to breathe. All we need to do is let our autonomic system do its thing.

Like the air, love is always there for us, unconditional. We only need to open our nostrils, throat and lungs and breathe: love in, love out.

Of course, neither air nor love are always entirely wholesome. We have polluted air and we have polluted love. Most people some of the time have moments when they find it hard to breathe—most people some of the time find love hard to feel, detect, receive or return.

But tapping off another living being’s supply of love is akin to standing on the hose that pumps oxygen into the lungs of a ICU patient.

Maybe, I thought one morning as I awoke from an aural dream, maybe I’m worrying too much. Maybe I’m trying too hard. Maybe I don’t have to do anything for love except let my autonomic system do the easy work: breath in, breath out.

The out breath is important. We can’t stockpile air: we’d explode. We can’t stockpile love either. Love is desperate for circulation. Without circulation, the whole system breaks down. So we don’t hold our breath: we breathe out.

My breathing is shallow. Next time I’m standing by the sink or staring into the pixels, I’ll imagine I’m breathing in all the love in the world—wouldn't I breathe deeply then?

And wouldn’t I breathe out as deeply, because I want to share this carbon with the trees and this love with all living beings.

Can’t even…

These three things have helped ease me through the week.

1. The Science of Laughter

In The Infinite Monkey Cage, Robin Ince and Brian Cox find out what makes people laugh and why. Pretty interesting for a comedy writer.

2. Hedgehogs and foxes

Are you a hedgehog or a fox? It’s a question that goes back to an Isaiah Berlin essay and one that helped Malcolm Gladwell determine that he was destined to become a journalist, not an academic.

A fox knows many things, but a hedgehog one important thing.

The distinction is wafted at, but totally unexplained, in this slightly unhinged profile of Gladwell in the Independent. The most interesting thing Big Malc says is when he’s asked whether he has ‘a gift’ for writing:

[I]f someone worked really hard could they write like me? Yes. But it’s a bit like saying, if someone worked really hard they could have your personality. My writing is who I am. Is good writing available to a larger group of people than we think? Absolutely. But the amount of work that goes into my writing... The last piece I did was 12 drafts, and if you write 12 drafts, I guess it’s going to be a pretty good piece, but how many people will do 12 drafts?

It’s not a style; it’s who you are. It’s not a gift; it’s hard work.

Which brings me neatly onto…

3. The value of persistence in comedy writing

I’m currently reading Good Habits, Bad Habits by Wendy Wood, one of the world’s leading social psychologists. She describes one piece of research that shows how we consistently underestimate the power of persistence.

At Northwestern University, Brian Lucas and Loren Nordgren asked a group of comedians to come up with as many punchlines to a setup as they could in four minutes.

Then they had to stop and tell the researchers how many more ideas they could come up with if they carried on for another four minutes. Typically, the comedy writers reckoned that they’d come up with fewer ideas after the break.

But when they were forced (presumably at gunpoint) to work for another four minutes, the comedians actually came up with more ideas than they expected—almost as many as in the first burst of creativity.

Lucas and Nordgren’s follow up studies showed that we particularly underestimate the value of persistence for creative tasks. In one experiment with over two hundred participants, the responses generated while persisting with the task in the second time period were significantly more creative than the responses generated initially.

The well doesn’t run dry, it runs deeper.

You can read a nice summary of Lucas and Nordgren’s work here. I’ve doubled the duration of my work sessions from 45 to 90 minutes.

Full marks…

1. For helping refugees beat tech inequality during lockdown

Can you imagine not having the internet right now? Staff and volunteers at Bristol Refugee Rights are calling up to a 100 elderly asylum seekers, single mothers, people with disabilities or mental health issues a week to provide wellbeing services and combat isolation. You can help fund their work. Thanks to Bean for sharing!

2. For helping us get better protection for cyclists and pedestrians

The UK government has promised us £2bn to help make cycling and walking—let’s be honest—safe. This includes £250m for emergency protection for cyclists and pedestrians while we still have to observe social distancing regulations.

Cycling UK has done all the hard work so that it’s easy to ask your local councillors for quick action to turn dangerous roads into safe spaces for self-powered citizens.

3. To the Israeli billionaire trying to solve Gaza’s water crisis—say whaaaat?!

If you think the past couple of months have been hard, spare a thought for the people of Gaza who have been living in lockdown for 13 years, thanks to Israel and Egypt’s air, land and sea blockade that stops almost anything from getting in or out of the Palestinian enclave.

As you’d imagine, the blockade has created multiple crises, the most awful of which is that Gazans don’t have reliable access to fresh drinking water. So Israeli billionaire Michael Mirilashvili has sent over a miracle machine that extracts potable water from the air. Like a massive dehumidifier.

According to this Times of Israel report, ‘he hopes to deliver enough units to meet the Strip’s daily needs within a year’.

This is amazing—although criminal that Israel took a year to grant permission for the machine and that it’s taken a private individual to show a little compassion. But there you go. Governments, huh?

Any more for any more?

I’ve started taking the prebiotic Biuma, a galactooligosaccheride powder that may possibly reduce anxiety and help give me better quality sleep. Science has been done. Biuma is made from cow’s milk and thus defiantly not vegan, but I care about my sleep more than I care about milking cows. Sorry cows. This experiment will last another 26 days, then I’ll make a decision on my non-vegan GOS future. For the geeks: before you write in recommending chicory root as an alternative, the prebiotic inulin found in chicory is a fructooligosaccheride for which no effect was found in the study cited above.

Either way, my experiment with Biuma has taught me a new word: borborygmus, previously known to me as stomach rumbling.

Much love,

dc:

CREDITS

David Charles wrote this newsletter. He publishes another newsletter about reading called Books Make Books. David is co-writer of BBC Radio Wales sitcom Foiled, and writes for The Bike Project, Forests News, Global Landscape Forum, Elevate and Thighs of Steel. He also edits books about adventure, activism and more. Reply to this email, or delve into the archive on davidcharles.info. Thank you for reading!

Unlock the commons for £30

These free weekly newsletters are currently 1.6 percent funded. You can unlock the commons for everyone by becoming a paying subscriber for £30 a year. Thank you.