Not The Best Medicine

You might meet today with ‘inquisitive, ungrateful, violent, treacherous, envious, uncharitable men’. Maybe they’re suffering from a twisted omohyoid.

Happy Friday!

Welcome to edition 311 and welcome to Costa da Caparica, Portugal. Caparica is supposedly named for the legend of an old woman who owned a cape that, on her death, shed enough gold coins to build a church.

Shedding gold coins or not, a cape would be pretty handy for the blustery showers blowing in off the Atlantic right now.

I’ve had a wonderful week of overland travel, from Paris to Portugal, via the Pyrenées.

Thank you to everyone who has hosted me and shown such kindness, generosity and patience, cooking, cleaning, translating, stethoscoping...

At some point, I may very well write up a semi-practical guide to the ease (or otherwise) of terrestrial international travel under Covid and Brexit, but that’s not today’s story.

Today’s story is about my ribs.

Not The Best Medicine

Science might say that laughter releases endorphins that support your immune system, can provide a palliative to long term illness, moderate sensations of intense pain and reduce your risk heart disease by relaxing your arteries.

Journalists around the world have celebrated this vindication of the pernicious claim that ‘laughter is the best medicine’.

It’s all lies.

When you have an intercostal muscle injury, laughter is manifestly not the best medicine.

In this case, laughter is, almost literally, side-splitting.

If humans have personalities, so do muscles. Some are extroverts, showing off their range and power, like the hamstrings or the biceps, making their presence felt with almost every movement of your body.

But some are introverts, happiest when unnoticed and, like the muscles of the eyeball or the omohyoid, scarcely ever consciously felt — until something goes wrong. Then: beware the quiet ones.

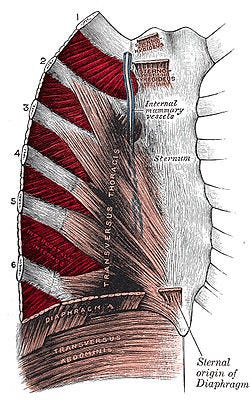

The intercostal muscles of the rib cage are introverts.

Their job is to help you breathe by expanding and contracting the rib cage so that the lungs beneath can fill and empty of air.

In the same way that a hamstring injury doesn’t necessarily mean you have to stop walking, so too an intercostal injury means that you don’t necessarily have to stop breathing.

What it does mean (in both cases) is that you should avoid explosive exercise.

In the case of a hamstring injury, now is not the right time to go sprinting.

In the case of an intercostal injury, now is not the right time for the six bodily functions that make life worth living:

Yawning before sleep

Hiccups after drinking

Burps after eating

Laughter with joy

Sighing in peace and contentment

Is there a more important muscle group than the one that helps suck in the air, not only of survival, but of life?

It started with a hiccup

It all started with a hiccup. Not a particularly large or loud one, just a normal hiccup on a hilltop near (appropriately enough) Rudenoise in France.

I felt a twinge in my side, but nothing more. The next day the twinge grew a little worse, but nothing insurmountable. I’d also pulled a muscle in my calf on the same walk. No big deal. I can walk it off.

The problems really started on Friday night, when Tim and I started trawling through our back catalogue of Abandoned Rugs songs.

There are many types of laughter. Some laughter is a social lubricant, either totally or partially under conscious control. This kind of laughter is fine.

But there is a laughter that is orders of magnitude more violent, more explosive and almost completely involuntary. More like a sneeze, in other words. This is what the songs we made with Abandoned Rugs do to me.

Now, these songs won’t necessarily make you laugh quite as much as they make me laugh. But imagine being six years old again. Go back to your most childish, playful self.

Now give your inner child unfettered access to an array of musical instruments, recording equipment and one very talented musician.

If I were to die and the only artefact to survive the centuries, from all my decades of creative work, was ‘Walking In The Area’ by Abandoned Rugs, I would die contented.

The magic of Christmas reduced to the banality of boredom and the sheer absurdity of trusting me (of all people) with the parody of a famous choral soprano leaves me helpless.

I’m standing on the grass,

I’m standing near the garden shed…

Professionally, I’m sure I’ve done better work, but nothing so reliably reduces me, personally, to paroxysms of laughter.

Unfortunately, such laughter rips into my intercostal muscles with uncontrollable and terrible force.

Laughing myself to death

The next day I catch the train down to Basque country. On Saturday night, I sleep fitfully and wake up almost in tears, unable to even roll over to get out of bed.

Luckily, I’m staying with a GP and, with the help of some serious Spanish painkillers, bought to ease my friend through the Camino, I feel much better on Monday and Tuesday — as long as I don’t go much further than a polite chuckle.

On Wednesday, however, I arrive in Lisbon. For some reason I decide not to take any painkillers. Despite the fact that I am here to spend a week with my comedy writing partner Beth Granville and our friends, writing funny jokes that make people laugh uncontrollably.

It’s a disaster. I manage to hold it together enough to survive the first course at dinner. Then I share a story about an ex, a bath and a game of chess…

Doubled over in the restaurant, struggling to breathe, not because I’m overcome by laughter, but because my lungs are unable to expand enough to draw oxygen into my blood cells through the pain.

It’s at this point that I wonder whether laughing oneself to death is a thing.

The Internet isn’t reassuring on this point. Aside from kuru, a devastatingly sad ‘laughing sickness’ caused by the consumption of diseased human brains, there are multiple cases of cardiac arrest caused by excessive fits of laughing:

Asphyxiation caused by laughter leads the body to shut down from the lack of oxygen.

I must remember to keep taking painkillers.

Personality is physicality

I sincerely hope that you never have to spend time with an injured intercostal muscle, but there is a broader lesson here, one that I hope everyone can sit with today.

The lesson is: personality is physicality.

I know this only too well from my experiences with my thyroid. An underactive thyroid makes you cold, tired and unable to focus. Not the best conversationalist. Physicality is personality.

In the same way, with an injured intercostal, I can feel myself consciously measuring my responses to other people. It’s simply too painful to let go and laugh with my friends. I can do a half-hearted chuckle — but who wants that?

I notice that I’m holding back from saying things that I know the other people will find funny because I can’t risk the laughter tripping my muscles. It’s a whole new way of being in the world (and a bit of a shit one). Personality is physicality.

In the same way that mountains, valleys and the ocean play a decisive role in our experience of clouds or sunshine, so too does the morphology of our bodies influence our own psychological weather.

There’s no point ignoring the basic principles of our existence, our facticity.

If you’re feeling irritable, maybe you need to be kinder to yourself. Stop pushing so hard. Ease off for a minute. Your body needs a break and your mind is responding with antisocial behaviour, in the hope that you’ll isolate and rest.

And vice-versa. You might, as Marcus Aurelius wrote, meet today with ‘inquisitive, ungrateful, violent, treacherous, envious, uncharitable men’. Maybe they’re suffering from a twisted omohyoid. Try empathy before anger.

Right, that’s it! I’m off to eat breakfast, take painkillers (the discomfort does seem to be easing) and walk beside the Atlantic. Over there, improbably, are the Americas.

Something is on the horizon.

Big love,

dc: