Competitive Generosity

The older I get, the more important it becomes, not simply to get out of my head, but to get into my body

Happy Friday!

And welcome to the Gipsy Palace.

A while ago, I was invited to contribute to a Red Pepper magazine retrospective on what a bunch of academics and activists learned from Debt: The First 5,000 Years, by anthropologist all-star thinker and doer David Graeber (RIP).

Well, the article has just been published: Learning from David Graeber.

I’m thrilled that Red Pepper gave my bit the headline ‘Debt is bollocks’ and honoured they decided it was good enough to open up the article — but there are many more worthy contributions from folks who knew DG far better than I ever did.

Not least Nika Dubrovsky, David Graeber’s partner and collaborator, who gives us an insight into the process of writing and publishing Debt:

As we waited for publication, David was increasingly nervous; he complained to me he needed to publish the book to change public discourse and the time was right now. He was right: the book, published in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, provided a new vocabulary needed to explain a changed world.

Today this new language—on how we understand debt—is used by everyone, including by power itself. This is what David called a revolution. He said revolution is not when palaces are seized or governments are overthrown, but when we change the ideas of what is common sense.

First, go and read our Red Pepper retrospective — I love Christopher J Lee’s bit about practising competitive generosity over competitive accumulation — and then go and read the book itself.

The full text of Debt: The First 5000 Years is available free online at the Anarchist Library.

For those of you new around these parts, welcome 👋 My name is David and I’m a writer, outdoor instructor and cyclist-at-large with Thighs of Steel. I write stories that help you and me understand the world (and ourselves) a little better.

Sometimes I write about the bollocks that is debt.

Welcome to edition 365.

Days Of Adventure 2023: 35

🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢 🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢 What is this?

Graham Eating Chips And Gravy

It’s not every day that you meet a motorcycling electrician called Graham eating chips and gravy in the sunshine at a village tearoom in Northumberland.

In fact, I’d say that it’s only ever happened to me once in my whole entire life.

Just once. Last Sunday.

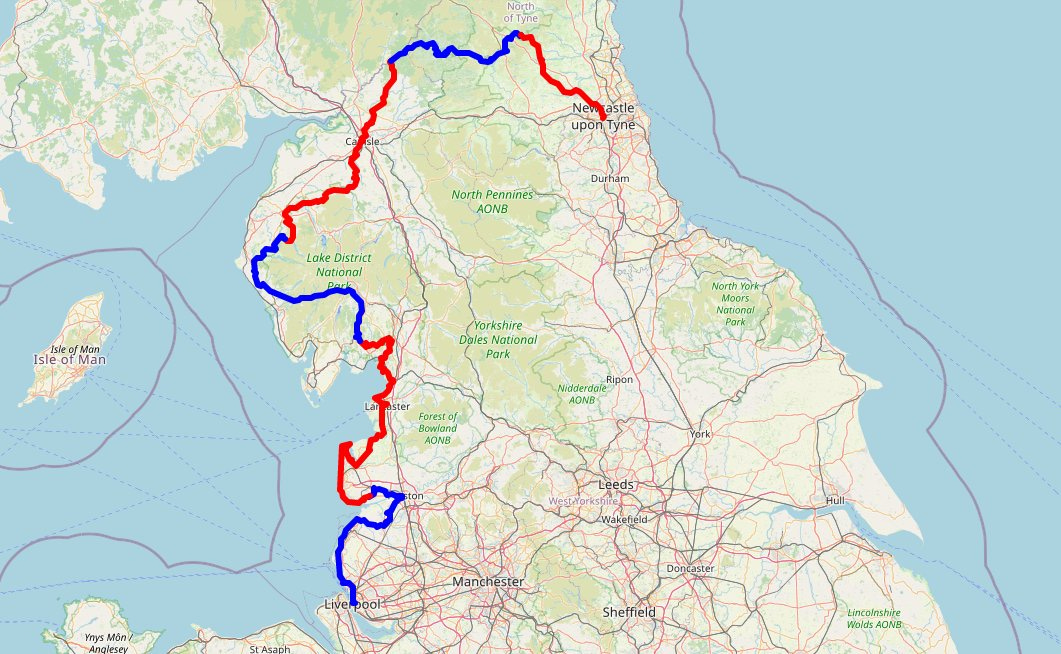

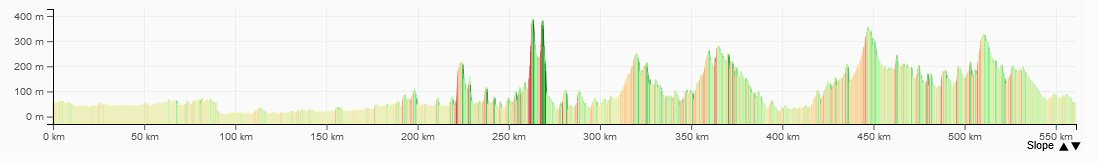

I was about 470km into my 560km ride from Liverpool to Newcastle and had just decided that it was time for lunch. Again.

Because, you see, If I’ve got any Northumbrian cycle touring advice for you it’s this: whenever you see a tearoom, it’s time for lunch. Again.

Quick Detour Regarding Bloody Bush Road (Unsurfaced)

Northumberland is the least densely populated county in England, with only 62 inhabitants per square kilometre.

This is an incredibly misleading statistic.

Across a 36 kilometre stretch of my route, on the terrifyingly named Bloody Bush Road through the high pine forests of Kershope, Newcastleton and Kielder, there were precisely zero inhabitants per square kilometre.

This means I went five hours of riding and sixteen hours overnight without refilling my water bottles.

Parched. Slightly panicked.

It was only at the very end of the rocky gravel track that I found a sign warning me against the route I’d just taken — READ THIS BEFORE RIDING —

This route is 20km through remote forest areas on unsurfaced tracks and narrow paths.

This route includes steep climbs and crosses exposed open hills and fells. It is therefore better suited to proficient cyclists with higher levels of fitness, stamina and good off-road riding skills. Quality off-road bikes are considered to be essential.

No water, no food, no phone reception and no houses except a couple of eerily abandoned rental cottages: this was not the place to hurt one’s self.

About halfway through my unwitting 20km off-road stint, rolling downhill on the gravel, my unsuitable road tyres skidded.

As the heavy bike slid out from underneath me — threatening to crush my leg under the weight of all my camping gear — my instincts took over.

Without knowing how, my left foot hopped onto the falling cross bar and I leapt over the moving handlebars, miraculously landing in a running stumble, on both feet.

I got away with it this time.

My dusty dry throat was finally lubricated at The Forks, a clutch of forest cottages, thankfully occupied (and each with a wolf-head door knocker), before rushing to the civilised and fully stocked activity centres of Kielder Water.

Lesson learned: population density matters.

Back To Graham Eating Chips And Gravy

So that’s why, only half an hour after tea and scones at the Tower Knowe cafe on Kielder Water, I rolled to a stop outside Falstone village tearoom.

And that’s where, for the first time in my whole entire life, I met a motorcycling electrician called Graham eating chips and gravy in the sunshine.

Quick Detour For Some Miserable Setup

I left to come on this bike ride two days late.

I was originally booked to get the train up to Liverpool on the Monday, but I decided to delay for a couple of days.

Helping to organise Thighs of Steel — an eight week fundraising bike ride with over a hundred participants across eleven countries — is a rat’s nest of responsibility.

Many aspects of facilitating the organisation of the ride are totally within my control: choosing dates and routes, finding ride leaders, paying staff, planning routes, recruiting riders and, of course, fundraising.

But some aspects are wildly out of my — or anyone’s — control. For the past six weeks, I’ve been wrestling with such a task.

And here it was again, that task, demanding more time from me and, if not forcing, then at least prising two days’ holiday from my short break.

Actually, this sacrifice of two days was actually pretty good going for me. In 2022, I would’ve cancelled the whole holiday.

Last year, I felt as much responsibility for the organisation of Thighs and the stress I held manifested itself as a dumpy lethagy and a claggy brain fog.

In my fatigue, I made the mistake of cancelling any extracurricular activities and staying at home, hoping to rest and recovery in the quiet hours when I wasn’t working.

I even took two courses of antibiotics, before realising that my symptoms were ‘just’ stress, far beyond the reach of pharmaceutical treatment.

I learned that, in the responsibility of a stressful situation, my mind and body tend to hunker down, shutting off function in the hope that, by hiding away in stillness, the danger or threat will pass by safely.

While this avoidant strategy might have worked for me in the past, it’s exactly ZERO percent fun and, in most grownup cases, leaves the problem worse than before.

What helps are precisely the things that, last year, I cancelled: seeing friends, playing games, going dancing and, of course, riding my bike for days at a time.

Anyway: turns out that Graham, the motorcycling electrician eating chips and gravy in the sunshine, goes through the same damn thing.

Graham Eating Chips And Gravy

Graham, a man with spectacles and the lived-in look of late middle age, arrived in his leathers and backed his motorcycle into the small parking lot beside the tearoom’s outdoor toilets.

He ordered chips and gravy and a coffee for afters — ‘I’m in no rush here.’

We sat outside, on high stools, with our plates resting on a waist-high sandstone wall, looking out over the shaded village green.

Graham had come up from Sunderland, a trip he often makes on a weekend. He likes to get to the tearoom before twelve, in time for their to-die-for breakfast.

He’s far too late today, which is why turns down their offer of a bacon barm — I can make that at home, like — and settles for chips and gravy.

Graham tells me that he’s an electrician, working for himself, but through an agency, mostly industrial.

I’m not sure what I imagine an electrician doing all day (I know it can’t only be lightbulbs and 3A plugs), but it’s nothing like what Graham does.

He’ll spend weeks wiring up identical units on an industrial site, ticking off the cabling on a schematic works sheet.

None of his work will connected to power until long after he’s gone, so he has to get it right, maybe not first time, but reliably, every time.

A lot of other electricians say they don’t have the patience for it, they get bored, but Graham likes it. It suits his methodical mind and that means he’s never short of work.

Graham felt he had to get out on his bike today: he’s got a job starting tomorrow, a job he already regrets taking.

He holds up thumb and forefinger, about a chip’s width apart: ‘Summer’s only this long up here.’

‘The agency said it’s a two month job, but that doesn’t mean anything. Could be two days, two weeks — two years,’ he says.

‘They said I could have a week off after a month, but that’s...’ He looks over at me, a little desperately. ‘I don’t want to put a time limit on it, you know?’

‘That’s My Sign I Need To Get Away’

Graham is out on his bike for the same reason I’m on mine: it’s his way of getting back into his body, opening up and letting go.

He’s learned to heed the warning signs and take to two wheels before things get worse.

A couple of years back, after his mother died, Graham was on a six-month job on the coast near Edinburgh.

As the months rolled on, he started getting a thick knot of pain in the centre of his chest.

Nothing he did shifted the pain until, one day, he jacked in the job and went for a long motorcycle ride in a loop along the green border and up through Dumfries and Galloway.

‘I was on the road, coming out of Ayr, when I noticed it,’ Graham tells me. ‘The pain in my chest was gone. Completely gone.’

It’s then that I realise who we are: two men, strangers, telling each other how we fall apart. And how we might put ourselves back together again.

‘When I feel that in my chest,’ Grama says, ‘that’s my sign I need to get away.’

It’s the same for me: when I feel that heavy veil falling across my brain.

We shook hands, Graham and I, and swapped names.

‘Good luck with the stress,’ he said, as I took the steps down to my bike.

‘It’ll be straight back when I hit that hill,’ I said.

‘And then you’ll get rid of it again.’

Mind IS Body

That’s been my motto the last few weeks. It’s one I’d like to wear through the summer.

The brain is all very good, but it’s only a tiny part of how we think.

And the poor thing is terribly self-obsessed.

The brain has such an inflated belief in its powers that it thinks (ha) it can sort everything out on its own — and frequently overheats in the attempt.

But when I remember that brains only work well when the whole body is moving, then my mind flows again.

Instead of trying to brute force my way through life on brain alone, I should remember instead to feel my way through the world with all-body senses.

A long bike tour works, but so too does a regular morning run or evening stretch time.

The older I get, the more I learn and the more responsibility I take, the more important it becomes, not simply to get out of my head, but to get into my body.

Some Maps

That’s all for this week.

Thank you for reading and I hope you found something to take away with you.

This newsletter (and the writer behind it 👋) is 100 percent community supported. I don’t take a wage for my writing, only what appreciative readers choose to give me.

Even better —

⚠️ Make your contribution direct to this year’s Thighs of Steel fundraiser ⚠️

If you’d rather I got paid, then it’s easy for you to give what you feel is right:

There’s also a tier where you can pay £50 or more.

Whatever you choose, thank you.

Big love,

dc: