Broken in

This week: Killer Coke, Ten Tors, soil inoculation and a world without email?

Happy Saturday!

And welcome to edition 265—coincidentally also the designation of the famous 1916 legal challenge United States v. Forty Barrels & Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola, in which the government failed in its attempt to remove caffeine from the soft drink. (The company had already removed cocaine from its recipe in 1905.)

Of course, it’s impossible to mention the world’s most terrifyingly popular belch-birthing beverage without also mentioning Coca-Cola brand ambassador Mark Thomas’s 2007 investigation for Channel 4’s Dispatches.

In the research for this particular rabbit hole, I was surprised—and grimly pleased—to discover that the Killer Coke campaign is still punching back.

Now, on with the show!

🥾 Read this story on my website

Broken in

Finding suppleness of mind and body in post-lockdown Dartmoor

Here in the UK, this was the week that we unlocked a little more. As I write, a paraglider drifts past my eighth-floor window. On my run this morning, the promenade was spilling over onto the sand and the bucket and spade buccaneers were doing a fast trade.

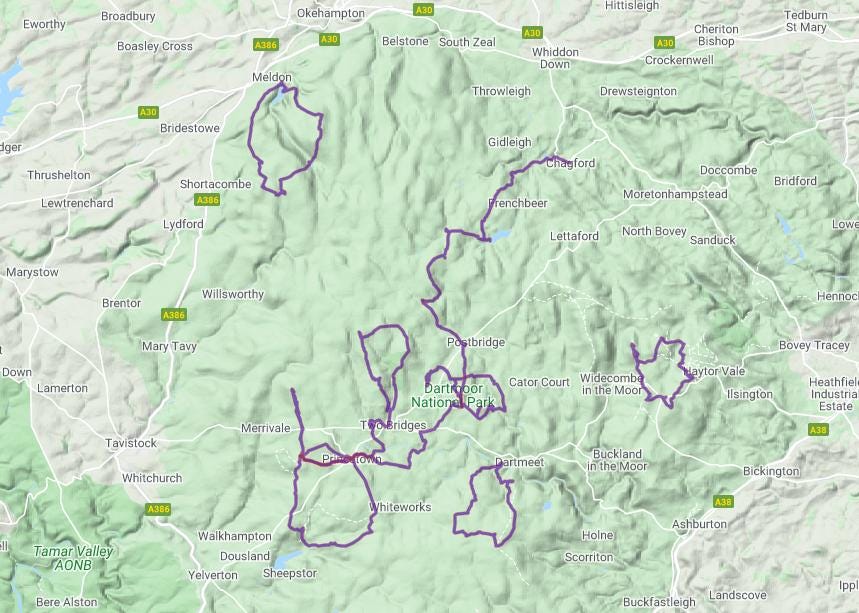

I’m late coming to you this week because I spent the last five days getting sunburnt on Dartmoor. As some of you know, I’m slowly working my way towards my Hill and Moorland Leader Award, chipping away at the forty logged walks needed before my assessment.

But the weather was so good this week that I worried my four hikes weren’t particularly good practice for the ultimate examination that will doubtless be undertaken in the filthy conditions for which Dartmoor is famous. Nevertheless, I’ve got only sixteen more training walks to go!

What I really valued about this week, however, was the feeling of breaking myself in again after a winter of semi-enforced inactivity. The sun rising over the horizon every blue-sky morning took on metaphorical overtones as I stood out in the chill dawn with a mug of tea and the birdsong.

Day three was the one that really did it for me. On day one, a fifteen kilometre tramp to the rising of the Avon river, I was powered by first day enthusiasm. But my enthusiasm drained overnight and, on day two, my feet dragged. I only survived a tour of Bellever and Laughter thanks to the morning addition of a hearty walking companion.

Resting atop Bellever, we watch a young boy hopping around the enormous boulders of granite, chasing the family dog. Mother, leaning back after lunch and looking up to us for solidarity, says: ‘Be careful—remember he’s got four legs, not two.’ But boy scrambles after dog. ‘These are too easy,’ he complains. ‘Can we find harder ones?’

Out loud, I suggest Great Mis Tor and the Devil’s Frying Pan, but what I’m wondering inside is whether I’ll ever have that boy’s energy again.

I perked up later in the evening after lighting the wood burner, but I was concerned for day three: did I have the strength to hike alone for four or more hours? Especially as, for some unknown reason, I’d decided to hike up the steep face of the moor’s highest peak, Yes Tor. It was yes again to my friend’s sound advice: ‘Go slow and take plenty of breaks.’

Trundling up the slopes from Meldon Reservoir, I ran into packs of army recruits, themselves making the most of a lifting lockdown. But as I clumped down the other side of High Willhays, I had the moor to myself, with nary a sheep to be spotted.

Somewhere between the solitude and the sunshine, the air and the exercise, I noticed that I hadn’t felt better in months. The stiffness of my mind and body had given way to suppleness, broken in.

When I made it back to base, after five and a half hours, eighteen kilometres and over six hundred metres of climbing, I felt stronger than when I’d left that morning.

The next day, we stopped at Haytor Rocks and spent the heat haze of Friday afternoon clambering around a mini version of the Ten Tors. Five hours down the trail, number ten on the horizon: from my lookout post in the clear blue sky, I see myself leaping from granite to granite, forever young in springtime.

Thanks to G.C. and B.Q. for fine company and penguin packets.

Can soil inoculation accelerate carbon sequestration in forests?

Good question! Answered by people cleverer than me.

When foresters first tried to plant non-native Pinus radiata in the southern hemisphere, the trees would not grow until someone thought to bring a handful of soil from the native environment. “They didn’t know it then, but they were reintroducing the spores of fungi that these trees need in order to establish,” Colin Averill, ecologist at The Crowther Lab, explains. “When we plant trees, we rarely ‘plant’ the soil microbiome. But if we do, we can really accelerate the process of restoration.”

📧 Read this story on my website

A World Without Email?

I took far too many books away with me this week, including three about the people and places of Dartmoor—but I only read one: Cal Newport’s A World Without Email.

Newport’s provocation was supported, not only by numerous case studies of organisations that have eliminated email, but also by psychology research and, most interestingly for me, history.

I was startled, for example, by the discovery that email overwhelm and inbox bankruptcy wasn’t merely latent in the system, but already evident from the very beginning, as this anecdote from the book shows.

When Adrian Stone implemented the new email network at IBM in the 1980s, he carefully estimated the number of emails that the server would need to handle, based on the number of telephone and paper messages that were passed between IBM employees on a typical working day.

Email was seen as a significant leap in efficiency for the company, removing the logistical complications of both synchronous communication (pinning someone down for a phone call or meeting) and asynchronous communication (delivering a pen and paper message).

Unfortunately, as the cost of communication dropped to zero, the number of messages the employees exchanged shot up and, within a few days, they’d blown the email server with the superfluous cc’ing of colleagues into endless back-and-forth email threads. Sound familiar?

As Stone puts it:

Thus—in a mere week or so—was gained and blown the potential productivity gain of email.

When IBM discovered this fundamental flaw with email, of course, they abandoned the experiment and everyone went back to communicating face-to-face, person-to-person in the old, slow, productive fashion. Oh, no, wait…

Luckily, in the second half of A World Without Email, Newport suggests alternative workflows that don’t provoke the misery-inducing ‘hyperactive hive mind’ of email and instant messaging.

I’m conscious of the irony of recommending this book in an email newsletter, so—before you unsubscribe—it’s worth saying that the title of Newport’s book is, by his own admission, more marketing hype than practical proposal.

Email still has a (drastically limited) role to play as a versatile, snappy, cheap tool for asynchronous communication. Inspired by the Reach Out Party, if I could declare one inviolable rule for every email interaction, it would be this:

Make your recipient’s inbox a better place to hang out.

That’s what I strive for with this newsletter. Remember that these stories are opt-in and you are free to unsubscribe at any time with my blessing.

But if these emails do make your inbox a better place to hang out, then I would be thrilled if you somehow show your appreciation. So many of you do and it means so much to me. Thanks!

Have a great weekend!

Big love,

dc:

CREDITS

Hello, I’m David Charles and I’m a UK-based writer and outdoor instructor. Say hello by replying to this email, or delve into 500+ other articles on davidcharles.info.

12 percent funded ▲▲△△△△△△△△△△△△△△△△△△

These free weekly emails are supported by readers who scroll all the way to the bottom—readers like you 😁 Help unlock the commons by becoming a paying subscriber for £30 per year—about 58p per newsletter.

Email land is 100% better when your newsletter appears! ❤️🤓

The one email in my inbox I look forward to reading each week!