An Oxytocin-Fuelled Haze Of Euphoria

A story about being overtaken by excitement in the company of strangers

Happy (Good) Friday!

And greetings from beachside, back from the Alps, in Bournemouth.

It must be a Bank Holiday weekend because we couldn’t find anywhere to park within 500m of home when we got back last night.

The beaches are also gratifyingly busy: we have here a sunny Bank Holiday, no less.

The street outside my window, besides the cars cruising aimlessly for any space to pull over, is aflow with flipped baseball caps and face-hiding shades, parents swinging kids swinging buckets and spades.

It’s got the quiet, solemn air of a day with serious nothing-to-do.

And yet here we are — hello, you! 👋 My name is David and I’m a writer, outdoor instructor and cyclist-at-large with Thighs of Steel. I write stories that help you and me understand the world (and ourselves) a little better.

Sometimes I just want to write something nice about the weather.

Welcome to edition 355.

An Oxytocin-Fuelled Haze Of Euphoria

As close readers among you will know, I’ve spent much of the last week in France, visiting friends (👋) in Paris and Chamonix.

If you’ve never been, Chamonix is a terrifying place where people don practical clothing and highly impractical footwear and then throw themselves off actual mountains in a variety of increasingly outlandish ways — strapped to two metal prongs or a single fibreglass plank, dangling off a rope, sometimes deliberately not dangling off a rope, tied with string to an enormous silk bedsheet or, for the truly deranged, wearing nothing more than a big coat with flappy bits, before launching themselves into the sky.

Suffice to say, I did not do any of that. To be honest, even the cable car was a bit much, at least on the way up.

On Monday, however, we took a genteel train (firmly on rails, I noted) from Chamonix up to Montenvers, where the tail of the Mer de Glace shyly uncurls from behind a mountain, spitting out skiers and snowboarders in a gruntling manner that even I confess looks rather fun from a distance.

We ate sandwiches in the sunshine and then hiked back down to town through the snow.

But that’s not what this story is about at all. This story is about being overtaken by excitement in the company of strangers.

Nose pressed against the window of the train, moving slowly enough to catch the eye of passing pedestrians, passengers in crossing trains or midday quaffers at cafés, I started doing this thing that I’d forgotten I do — waving ecstatically, grinning like a loon and throwing out rapturous thumbs up and fist pumps.

Reactions were mixed.

It’s not standard behaviour for an adult, see. Not even for one wearing a bobble hat. Strangers don’t know quite what to do with the incoming data.

Shock and the moving train quite often left no time for any response, but my friend and I enjoyed watching those of relaxed and nimble mind move quickly from confusion, through panic and shyness, to why-the-fuck-not-wave-back?

A bolt of electricity passed between strangers and thus a moment was shared.

I learned this trick off a Polish bear-of-a-man called Marko who I met learning Arabic in Tunisia back in 2008. He was a charismatic fabulist with a thousand and one nights’ worth of tall stories and almost as many uses for the neat vodka in his everyday carry hip flask.

I was never quite sure how much of what he told me was true and how much of it didn’t matter that it wasn’t.

But I’ve never forgotten his audacity and penchant for giving strangers in the street a mighty white smile, thumbs up, high five or, indeed, shoulder bump.

It’s all about being deeply uncool, as confident-lunatic as you can be. And if it works in cooler-than-cool Chamonix, it works anywhere.

Even in London.

Flashback to 2013…

Way back in 2013, I was writing a book called You Are What You Don’t, about the art and science of positive constraints, imaginative twists on the unwritten rules of life.

I experimented with living without things like mobile phones and supermarkets, but also without abstract concepts like borders and walking. It was all about breaking my previously unexamined habits to learn what was really going on underneath (and whether, in truth, it’s more hygienic not to use toilet paper).

Then I decided to transgress that most London of social injunctions: There shalt be no smiling eye contact between strangers.

It all started halfway through reading the following convoluted sentence from the introduction to Mark Boyle’s second book, The Moneyless Manifesto:

While collectively taking off the lens called ‘How much can I get?’ and putting on another labelled […] ‘How many people can I make smile today?’ […] wouldn’t by itself cut the Gordian Knots of climate chaos, […] it would make for a crucial starting point.

Suitably inspired, I started logging smiles on my Nokia’s rudimentary spreadsheet function. I already kept track of all the money I spent, why not log smiles too?

‘I bet I can get a smile out of this’

The first sign that this was a project worth pursuing was on day one when I saw a man in his sixties help a woman with her heavy bag up the steps at Winchmore Hill station.

A few minutes later, I found myself walking behind the man towards my friend Beth’s house (👋). The path was too narrow to overtake comfortably, but he sensed me tripping on his heels, so he turned around and said something like, ‘You’re too fast for me nowadays.’

Normally, I would have just muttered a thanks and walked on, but this time I thought, ‘I bet I can get a smile out of this.’

So I slowed down to his pace and we chatted pleasantly, until we were both bowled out the way by a couple of kids hurtling down the path at us. We shared a smile and a laugh, and I added one to my spreadsheet.

What gets measured, gets motivated.

An oxytocin-fuelled haze of euphoria

I garnered a tidy eight smiles that first day and was pretty pleased with myself, fully expecting future days to hover around a similar mark or lower, considering I spend most of my life cloistered away in my lonely writer’s garret.

Little did I suspect that this innocent smile-gathering game would take total command of my life in an oxytocin-fuelled haze of euphoria.

The game lured me into doing pro-social smile-based deeds, like buying biscuits for an entire indie band I only vaguely knew (four smiles), and pressed me to turn rudimentary human interactions into fully-blown friendly encounters, including the somewhat risky manoeuvre of making my neighbour smile at the urinal.

There was no social opportunity too private to squeeze a smile from a stranger and I learnt that it’s even possible to smile down the telephone: the other person can always tell and, almost imperceptibly, the conversation lightens and brightens.

The Smiler’s Credo

By the end of the first week, I was regularly hitting twenty and thirty smiles a day and I’d developed a full-on smiler’s credo.

Remember, I told myself, even a single shared smile is infinitely and immeasurably precious. A moment spent smiling with another is a moment spent in the company of the divine.

Smiling, I decided, is defiance in the face of the hostility of the universe: it’s how we humans thumb our noses at the vanishing unlikelihood of fate that we should end up existing at all, never mind here and now, together in the same space-time.

If I knew that I could make a stranger smile as I passed them in the street, then surely I had an overwhelming responsibility to do so, without delay.

I’d catch people unawares as they walked from the station to work, sneaking smiles into their commutes. I’d change seats on the train once I’d smiled at all those around me: another carriage awaited my beneficence.

I knew nothing of these people’s lives, but I knew what a surprise smile from a stranger sometimes meant to me. On a dull day when the clouds cover our spirits, sometimes all it takes is an unexpected smile and the whole day can turn around.

‘I felt like the universe was falling into place for me’

One miserable evening, a wonderful friend (👋) was dumped by her now-verifiably-silly boyfriend.

My friend was devastated.

We sat together on my sofa as she cried on my increasingly soggy shoulder, but nothing would console her: neither sympathy nor indignation — not even chamomile tea.

But the next day, with hope in her eyes, she told me how she’d been on the tube, still desolate with her agony, when the man sitting across from her gave her a smile.

‘I felt like the universe was falling into place for me,’ she said, ‘That it was supporting me, right at the moment when I most needed it.’

Smiles are powerful, healing magic spells that we’ve all got, stacked up, waiting, ready to go, inside of us.

Infinitely renewable, sometimes they’re tapping on our teeth, bursting to get out, other times they’re lurking deep down somewhere next to our kidneys and it takes all our pushing to birth them into the world.

But please don’t let them fester from underuse — they’ll only grow mouldy down there and you might end up with some kind of infection.

It’s imperative we use them, throw them out with careless abandon, because none of us can ever know who will need our smile-of-the-moment most desperately.

You — little old you with the creaky knees and the occasional patch of eczema — you could be the nudge that makes the nigh-infinite universe fall into place.

A little jolt to the heart

One random Tuesday, I was smiling at people on the escalator, as they came up and I went down. Most stared dully back, or snapped their glance away like frightened marmots, but one woman smiled back and I felt an instant shot of pleasure.

I bounced off the end of the escalator, beaming: smiles beget smiles.

It wasn’t much, this little jolt to the heart, but it was something: I felt seen and acknowledged by another member of the human race and it felt very good.

These moments didn’t happen every time I won a smile, but they happened often enough and, without buying a ticket, you can never win.

If we fill our days with these moments, and recognise that by doing so we are also filling other people’s days with such micro jolts, then perhaps we can spread the revolutionary idea that life is, despite everything, at least occasionally worth living — not because everything is rosy and all our problems are solved, but because someone else, a stranger, is there with us, on our side.

It’s a Team Human thing.

How quickly can we change the culture of an entire city?

After a couple of weeks of smiling my head off, I decide to ramp things up. I start saying good morning to random people on the street.

The pleasure I feel, that jolt when another person responds in kind, intensifies.

Instead of turning inwards when the day starts badly, I turn outwards with a smile and a cheery, ‘Good morning!’

I become insufferable.

But I don’t care: it works. A greeting is even harder to dodge than a smile and my spreadsheet numbers jump up again. The positivity of connection electrifies and energises me for longer. I live for this shit now.

It doesn’t matter at all to me that the other people are strangers. In fact it seems to help: the smile or greeting is completely without precedent, free of social obligation, a completely unearned and unaccounted gesture of goodwill, no strings attached.

No strings, perhaps, but every smile puts out a slender filament, like the exploratory hyphal tip of an underground mycelial network.

A smile, you see, is contagious. A smile, even from a stranger, can override the control we have on our facial muscles: we simply can’t stop ourselves from smiling back.

So when someone makes me smile, I carry that smile along with me for a while, until it bursts out from me to someone else. And so it is that the levity of a smile travels from host to host through my neighbourhood to who-knows-where beyond.

A smile at a stranger communicates that you are not afraid, that you know they are friend not foe. It communicates to them that their community is around them and that their neighbourhood is relaxed, content and ready to support.

This sense makes me wonder about how quickly we could change the culture of an entire city.

Be more Egyptian

I've been lucky enough to spend a good chunk of time in a few different countries, with very different cultural norms when it comes to interacting with strangers.

Two stand out in my mind: Egypt and Andalucía, Spain.

In Egypt, it is considered rude not to personally greet everyone when you enter a room, whether you know them or not. Try that next time you go down The Red Lion.

Those Arabic greetings are also much more meaningful than their desultory English equivalents (‘Alright’, ‘Hi’, ‘Morning’).

The polite greeting in Egypt translates as ‘Peace be upon you’, which is lovely, but pales beside the standard morning greeting, which comes as a call-and-response:

‘Morning of Goodness!’ you say.

‘Morning of Light!’ I reply, or perhaps ‘Morning of Flowers!’

It’s really rather pretty, when you think about it.

In Andalucía, I found that it’s customary to greet people as you sit down next to them on the bus. Public transport becomes an everyday opportunity for a good natter, whether they’re a stranger, a neighbour or that bloke you’ve seen about town who wears the hats — you know the one.

I returned from both trips a more polite, more gregarious citizen and I wondered: why is London not like this?

Even in Cairo, a city two or three times the size of London and infinitely more polluted, chaotic and stressful, people still greet each other as they cram onto or dangle off the side of the microbuses that weave in and out of thick traffic.

In London we keep ourselves to ourselves, and even folks from Andalucía know to keep their traps shut on the Underground.

A culture, evidently, dictates certain actions to its citizens, so that they ‘fit in’. These actions become habits: walk fast, head down, elbows tucked.

Whenever the possibility for human interaction becomes a real and present danger, hide your eyes behind your phone or, in extremis, behind a copy of the free newspapers that the authorities hand out on the street for that exact purpose.

These habits engrain themselves into our character, whether we want them to or not. We become avatars of the keep-yourself-to-yourself culture, and in so doing we help pull outsiders into alignment.

Changing a culture means changing the habits of its citizens, which starts with changing their actions: hard to do against the pull of the tide.

Recommended Daily Allowance

After a few weeks of counting smiles, I can pin point exactly how many I need per day to feel good about myself: twenty.

Less than twenty and I can feel a little grouchy and listless at the end of the day.

I can handle more than twenty, but a lot more can feel overwhelming. And no wonder: according to reports of a study funded by Hewlett Packard, a good smile (the highest scoring was Robbie Williams’s) can be as stimulating as two thousand bars of chocolate or £16,000 in cash.

Quality smiles can reduce the negative effects of stress, as measured by heart rate and cortisol, while increasing mood-enhancing hormones like serotonin and possibly reducing blood pressure.

Your smile can also determine how fulfilling and long-lasting your marriage will be (ahem, science) or even dictate how long you’ll live (according to one contested study that failed replication, but let’s not allow that to bother us too much).

Even if these scientific studies stretch and break the limits of their validity, wouldn’t you still rather live in a world where the wildest extrapolations of the power of smiles hold true?

For a month in 2013, I was there, in that world.

And, whenever I remember to do this thing that I forget I do, I’m back: in the forgotten world behind the rain and the umbrellas and the washed-out faces, behind the make-up and the masks.

The only thing we need to access this world, anytime, is the secret password. No one can change the password because the password is the same the world over — a smile.

~

Thanks to RK (👋) for hosting me in Chamonix and for joining me in lunatic connection with strangers. Thanks to CW (👋) and the whole MMT team who inspired the germ of this story — and thanks to my 2013 self (👋) for writing most of it a decade ago!

Days Of Adventure 2023: 14

🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢🟢 What is this?

I haven’t been up this high since I was six years old. Mountains are pretty cool, hey?

Three Small Big Things At The End

1. Cars On The Way Out In Paris Too

Following on from last week’s note about pedestrianism and cyclism in London, the same thing’s happening in Paris too:

[T]he Right Bank’s main east-west artery, the Rue de Rivoli […] has gone from six lanes of traffic (four moving, two parked) to one for taxis and buses, with the rest a bike path serving 8,500 riders a day. (In a pinch, the bike path is wide enough to serve as a traffic-free route for emergency vehicles; an analysis recently showed that this has helped the city lower fire response times to under seven minutes for the first time in more than a decade.)

2. Male Ambition Drift

This Anne Helen Peterson essay captures a lot of what frustrates me about Man Sloth Mode (including my own):

“Men don’t need ambition,” one reader told me, when we were discussing the ambition gender divide over on Instagram. “They have privilege. They rise unless they work hard at sucking.”

Except, increasingly, there are real world consequences for men without the ambition drive, without the capacity for organisation, planning and just generally making shit happen.

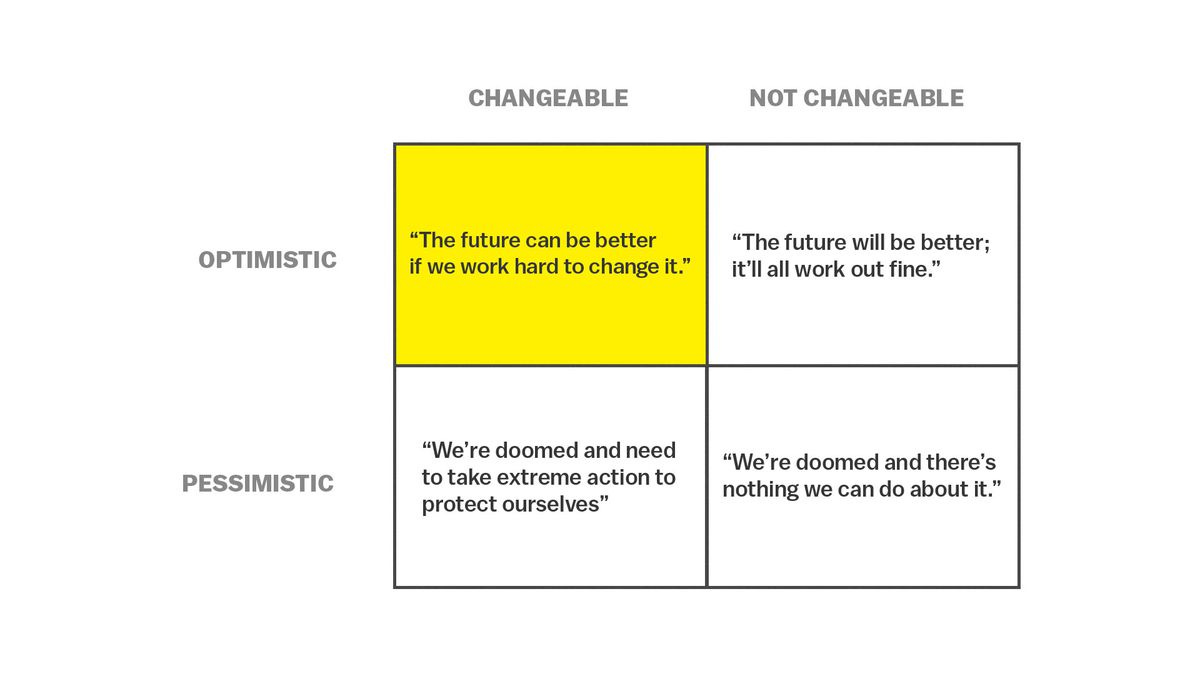

3. Against Doomerism

The Vox series Against doomerism is a nice companion to understanding the scourge of doomspreading. It’s heartening to see mainstream media both naming the phenomenon and, hopefully, helping to disarm those who choose to spread paralysing despair.

One small caveat: these Vox articles tend to echo the uncomfortable belief that human history amounts to little more than ‘tens of thousands of years of general misery’ from which humanity has been (and shall be) saved by technological progress (praise be to code).

I’m not sure about that, personally, but it’s still nice to remember that, with a little love and perseverance, each one of us can make life a little more beautiful for one another.

That’s all for this week.

I feel very lucky that I get to sit here and write to all 549 of you, picking up these words from 50 countries around the world.

That includes 6 of you 👋 spread among the 7,641 islands of the Philippines 🇵🇭, where (continuing my theme from last week) the oldest known written document is this c. 900AD hammered copper tablet that relieves His Honor Namwaran and descendents of salary-related debts:

But the tablet’s true importance is that its discovery in 1989 overturned the Western historical theory that, prior to the arrival of Spanish colonists in 1565, the Philippines were culturally isolated from the rest of southeast Asia.

The copperplate inscription shows that the Philippines were an integral part of the centuries-old, multi-cultural Indosphere that stretched in a loose necklace of principalities and empires across lands now called Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Cambodia and Vietnam. 🤯 OMG WE ARE SO CONNECTED.

Thank you for reading and I hope you found something to take away with you.

Don’t forget that this newsletter is community supported. It’s easy for you to pay what you feel it’s worth:

There’s also a tier where you can pay £50 or more. Whatever you choose, thank you.

Big love,

dc: