A Lot of Botany

As Camus might say: ‘One must imagine the moon happy.’

Happy Friday!

And a warm welcome from the Tower.

It’s been far too long since my last missive; so much water has passed under the bridge and we find ourselves once again in the last quarter of the moon cycle.

It’s reassuring to know that, while we’re rushing around getting life done, there’s at least one celestial body up there, plugging away at the same old orbit, with the same old sun on its face, first, full, last, new, from infinity to infinity, until the universe explodes.

As Camus might say: ‘One must imagine the moon happy.’

For those of you new around these parts, welcome 👋 My name is David and I’m a writer, outdoor instructor, cyclist-at-large with Thighs of Steel, Expeditions Manager at British Exploring Society, and Advanced Wilderness Therapeutic Guide in training.

Yes, that is too many hats.

In this newsletter, I write stories that help you and me understand the world (and ourselves) a little better.

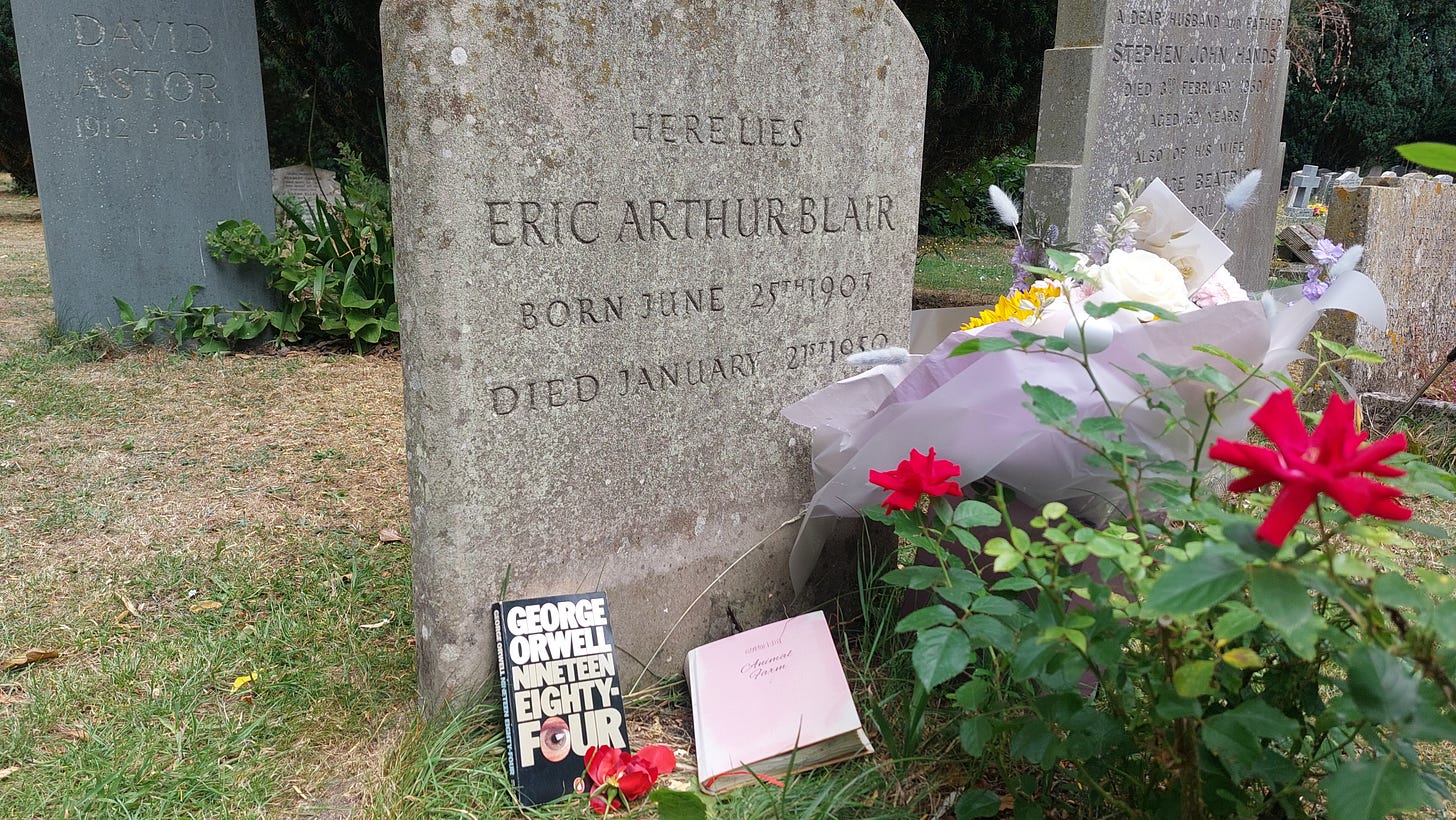

Sometimes I get interviewed by friends while visiting a famous grave.

A Lot of Botany

This week, I somehow passed the Level 3 Foundational Ethnobotany course, led by Legend of Bushcraft John Rhyder, ably assisted by professional herbalist Tim Lane.

If there’s one thing I’m taking away from this course, it’s that there is an awful lot of botany out there.

My motivation for joining the course was founded on two principles:

Plants are everywhere.

Plants do amazing stuff.

The first principle is something I’ve noticed on my travels. Maybe you’ve noticed the same thing?

The second principle is something I’ve toyed with — last winter we made a medicinal syrup out of rosehips I foraged from our local park, and we’ve gathered wild garlic and three-cornered leek for pesto and road snacks.

These smidges of plant knowledge were enough to tread a fine line of reasoning: if I could learn a little more about plants, then anywhere and everywhere becomes an amazing adventure playground.

Oh and John Rhyder’s course is an NCFE accredited certificate and I bloody LOVE a certificate.

The course took place over five days in Sussex, predominantly based in John’s woodland camp, with field trips to explore the habitats of nearby riverbanks and chalky downland.

Our days were divided between snail’s pace identification walks and practical preparation sessions, making tinctures, ointments, dyes, cordage, mats, bannocks, fritters, and something-or-other out of thistle.

In all, we covered the identification and practical uses of fifty-four plant and twenty-one tree species.

That’s seventy-five new species.

And July is supposed to be the leanest time of year for the forager.

These seventy-five species were thankfully pared down to a master list of thirty-three that formed the basis of our final day exam.

I’d known perhaps half of the master list before coming on the course — nettle and thistle, for example — and this proved just enough to utterly confuse myself.

When it comes to plants, my brain operates a strict ‘one in, one out’ policy.

Somehow I muddled through the exam, using incredibly professional identification mnemonics such as ‘bennie’s balls’ (Herb Bennet), ‘stinky pinky parsley bob’ (Herb Robert), and ‘if you touch that one and then rub your eye you will go temporarily blind’ (Hemlock Water Dropwort).

How many of these plants I retain only time will tell. But if I can use this story as an aspriational grimoire for beginners, I would lay out the following:

There are enough leafy greens out there for you to never buy a summer salad again. Learn what’s in your local park — dandelion is an easy win.

Nettles are the Swiss Army Knife of plants — and not only because they hurt you if you handle them wrongly. They’re high in protein and all kinds of vitamins and minerals. Cook the young leaves like spinach, toast them over a fire, or dunk them in tea. Make string out of the stems. When they’ve gone to seed, do everyone a favour and cut them back — they’ll grow back again in a few weeks, fresh to eat.

Similarly, lime or linden is among the most versatile of trees — and was heavily and handily planted in public parks across southern England. You can eat the leaves throughout the season and the flowers make an excellent anti-inflammatory tea for colds or anxiety. You can also strip the bark (on thin fallen branches) to make cordage — a hugely satsifying activity.

If you are ready for the next level: mugwort, wood betany and valerian are all worth gathering for sleepy, dreamy, relaxing infusions. Note that the ‘Four Fs’ — flowers, fruit, foliage and fungi — are fair game anywhere you have public access, but for valerian root you will need the permission of the landowner.

Whatever you gather, go easy — both on the plants and on yourself.

If you’re really keen, you can see some of my plant observations over on iNaturalist.

Thank You

Huge thanks to all the paying subscribers who helped make this story possible. You know who you are. Thank you. 💚

If you enjoyed this one, then go ahead and tell me. It’s the only way I’ll know. You can tap the heart button, write a comment, share the newsletter with friends, or simply reply to this email.

If you’re not into the whole Substack subscription thing, then you can also make a one-off, choose-your-own-contribution via PayPal. That’d make my day.

As always, thank you for your eyeballs and thanks for your support.

diwyc,

dc: