#97: The good life (and the perfect hummus)

Happy Friday!

Last Saturday I stuffed myself into Senate House banqueting hall with a few hundred philosophers and soaked up the ancient wisdom of the Stoics. Stoicon 2018 was upon us!

The more assiduous readers among you will already be well-aware of my fascination with this ancient philosophy. The more forgiving readers among you will indulge a short series of my reasons why, starting today with the brilliantly obvious Stoic idea of living in harmony with nature.

But first! Two quick and dirty reasons we should pay attention to ancient philosophy:

It's philosophy. Since when do we have time to think about such frivolities as how we might live a good life? Since now! As I wrote last week, we're already stumbling blind and mob-handed into the future - we might as well make sure it's a future worth living in.

It's ancient. Old ideas certainly aren't always the best, but they've got a much better chance of being among the best, having somehow survived the ravages of time. At the very least, it's worth listening to, just to make sure there isn't some nugget of wisdom to be salvaged.

And now Part 1 of Stoic Ideas I Like Like You (SIILLY) (title is a work in progress).

1. Live in harmony with nature

Stoics believe in the unity of the cosmos, a view consonant (incidentally) with both modern physics and ancient psychedelics.

Whether you prefer to imagine atoms arranging and rearranging themselves across time and space, or speculate on a universal consciousness, Stoics believe that the cosmos is one whole.

Hierocles, the 2nd century Stoic, imagined a series of concentric circles radiating outward from our self: our family, our friends, our neighbours, our countrymen - and so on to the outer limits humanity and beyond.

Stoics believe that our task in life is to bring distant circles closer and closer, until we treat everyone and everything as though they were our dearest family.

The Stoics often exhort themselves to 'live in harmony with nature' and, as a single community, it would make little sense to destroy or damage any other part.

What serves to maintain nature, is good for every part of nature.

- Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 2

On the one hand, we must not forget that humankind is a part of nature. So let's be a part of nature: accept that the laws of nature apply to us all, and that we are born, will suffer the vicissitudes of life, and will die and decay according to those rules. Don't rage against the laws of nature: accept your fate with a smile.

On the other hand, there is a clear implication that humans can behave in ways that are inimical to nature, and we should avoid these ways.

Living in harmony with nature could and should be interpreted in the strongest possible terms with regards to the health of the planet. For Stoics, it is an abomination to behave in ways that are deleterious to our present environment and the environment of future generations.

That's why to live in harmony with nature is SIILLY.

The Perfect Hummus

Cold water

8 ounces (227 grams) dried chickpeas

2 tablespoons plus 1 teaspoon kosher salt,

divided

½ teaspoon baking soda

¾ cup toasted tahini, room temperature

3½ tablespoons lemon juice

1 to 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 tablespoon chopped fresh parsley

½ teaspoon ground cumin

½ teaspoon paprika

In a large bowl, combine 8 cups of cold water, the chickpeas and 2 tablespoons of the salt. Let soak at room temperature at least 12 hours or overnight.

In a large stockpot over high, bring 10 cups of water and the baking soda to a boil. Drain the soaked chickpeas, discarding soaking water, and add to the pot. Return to a simmer, then reduce heat to medium and cook until the skins are falling off and the chickpeas are very tender, 45 to 50 minutes.

Set a mesh strainer over a large bowl and drain the chickpeas into it; reserve ¾ cup of the chickpea cooking water. Let the chickpeas sit for 1 minute to let all liquid drain. Set aside about 2 tablespoons of chickpeas, then transfer the rest to the food processor. Add the remaining 1 teaspoon of salt, then process for 3 minutes.

Stop the processor and add the tahini. Continue to process until the mixture has lightened and is very smooth, about 1 minute. Use a rubber spatula to scrape the sides and bottom of the processor bowl. With the machine running, add the ¾ cup of cooking liquid and the lemon juice. Process until combined. Taste and season with salt.

Transfer the hummus to a shallow bowl and use a large spoon to make a swirled well in the center. Drizzle the well with olive oil, then top with the reserved 2 tablespoons chickpeas, parsley, cumin and paprika. —J.M. Hirsch and Diane Unger

>> INPUT

[LONG READ] How the sandwich consumed Britain (The Guardian). A surprisingly profound exploration of how pre-packaged sandwiches went from nothing in 1980 to a £8bn a year industry. Choice quote: "Starbucks knows you are more likely to have a salad on a Monday, and a ham and cheese toastie on a Friday."

[WILDLIFE] A People's Manifesto for Wildlife (via Chris Packham, one of the editors) "A culture is no better than its woods" - WH Auden.

[BUSES] Pollution-busting bus hits the roads to clean up urban air (Positive News) "The filter then allows the bus to blow out more pure air so that the air behind it is cleaner than that in front of it." Awesome.

[REFUGEES] Choose Love "Every single purchase you make goes towards a similar item for a refugee, delivered via one of the 80+ projects Help Refugees work with across the world."

[STOICISM, OBVS] What is happiness? (Modern Stoicism, Stoic Week Day 1)

OUTPUT >>

The Victor Frankl 5-a-Day Book Cult: Day 22 (September)

Not-Gandhi was wrong: you already ARE the change (September)

The First Stile (September)

The Victor Frankl 5-a-Day Book Cult: Day 21 (September)

Black Sheep Backpackers: A Mild Review (September)

...COMING UP...

Thighs of Steel reunion ride tomorrow (£79,948.15 raised so far!)

Dartmoor for a spot of Hill and Moorland Leader training from Thursday

Now On: The Victor Frankl 5-a-day Book Club!

Membership Criteria: Read 5 pages a day of Man's Search for Meaning to complete the whole darn text in only 28 days. I'll be tootling through the text at just 5 pages a week, so you've got plenty of time to catch up online.

Day 23

Today's pages (p119-125) begin, strangely enough, with something of a lament for the loss of clergymen as a professional resource for treating a loss of meaning in life. Today, instead, people turn to psychiatrists (and are frequently mistreated for neurosis, is Frankl's implication).

After making the point that life's duration has no bearing on its relative meaning, Frankl turns to the troublesome (for a scientific mind) metaphysics of what he calls 'super-meaning'. He begins by posing a reasonable question:

Are you sure that the human world is a terminal point in the evolution of the cosmos? Is it not conceivable that there is still another dimension, a world beyond man's world; a world in which the question of an ultimate meaning of human suffering would find an answer?

The only reasonable answers that a man of either science or religion can make to these questions is: 'No' and 'Yes'. However, although Frankl is a religious man, logotherapy does not depend on religion. It depends merely an acceptance of mystery so that we may avoid the Existentialist alternative of surrendering to the meaninglessness and absurdity of life.

Because Frankl's ultimate meaning 'necessarily exceeds and surpasses the finite intellectual capacities of man', all logotherapy asks of us is that we are able to accept our 'incapacity to grasp [life's] unconditional meaninfulness in rational terms'.

Frankl openly admits that this acceptance, and thus the full power of logotherapy, comes much more easily to his religious patients. The ambiguity of the super-meaning will be more or less of a problem depending on your own religious and scientific proclivities.

Today's section ends with a fine discussion of aging and the transitory nature of our existence. For Frankl, our aging and death makes our lives far from meaningless - so long as we take responsibility.

[T]he only really transitory aspects of life are the potentialities; but as soon as they are actualised, ... they are saved and delivered into the past, ... [where] nothing is irretrievably lost but everything irrevocably stored.

It's a remarkable claim - that the actions we take in our lives are stored like memories on the hard-drive of the world - but it's one that stands up to reason. The consequences of our actions might be imperceptible to us, but no one can deny that they each have some bearing on the course of the universe. Even if we simply doze the afternoon away, we are still actively not doing a million other things and a million potential futures vanish.

At any moment, man must decide, for better or for worse, what will be the monument of his existence.

This could sound like a very heavy existence indeed, but its gravity or levity depends more on how one carries oneself. And from this perspective, aging becomes a comfort, not a cause for existential angst.

The pessimist resembles a man who observes with fear and sadness that his wall calendar, from which he daily tears a sheet, grows thinner with each passing day.

On the other hand, the person who attacks the problems of life actively is like a man who removes each successive leaf from his calendar and files it neatly and carefully away with its predecessors, after first having jotted down a few diary notes on the back.

He can reflect with pride and joy on all the richness set down in these notes, on all the life he has already lived to the fullest.

(Is it coincidence that this optimist sounds a lot like a psychiatrist, filing notes?) No matter - Frankl imagines that optimist looking back from old age:

"Instead of possibilities, I have realities in my past, not only the reality of work done and of love loved, but of sufferings bravely suffered. These sufferings are even the things of which I am most proud, though these are the things that cannot inspire envy."

And that, in a nutshell, is the worldview of logotherapy.

---

We continue next week...

Have a great weekend!

Much love,

- dc

CREDITS

David Charles wrote this. David is co-writer of BBC Radio sitcom Foiled, does copywriting for The Bike Project and is pretty much always available for work. davidcharles.info // @dcisbusy

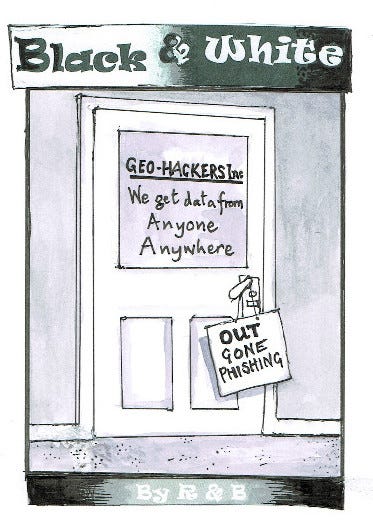

Courtesy of European Geochemical Society 'Elements' magazine. And my uncle.