#93: Community on Wheels + Murakami + The Victor Frankl Book Cult

Happy Friday!

Today is the final day of the epic seven week cycling relay fundraiser that is Thighs of Steel.

At about 5pm, the latest peloton of steely thighed cyclists will sweep into Athens, hot, sweaty and exultant after an 85km day's ride - the culmination of a journey that started 4,600km ago in London.

The bike ride, and the 80-odd riders thereon, have already smashed their target of raising £50,000 to pay the bills at refugee community centre Khora - and are pushing on to beat the record set last year of over £100,000.

These are the numbers. On the face of it, they sound very impressive. But, let's be honest, there are more efficient ways of raising money for charity.

A single fundraising soiree in the City of London could raise over a million pounds, and completely transform the operational capacity of Khora literally overnight. A bike ride is a painfully elaborate way of charity fundraising, no doubt.

Even the riders themselves are poorly chosen. My companions were teachers, counsellors, social entrepreneurs, itinerant festival workers. It wouldn't be hard to target a higher-earning bracket of cyclist and easily double or treble the fundraising target by tapping into a network with more money to give.

But that's not what the organisers have done, that's not what the organisers want to do, and that's not what the organisers have chosen.

They have deliberately chosen an inordinately long bike ride, they have deliberately targetted this motley demographic. None of this is an accident.

Thighs of Steel is not a fundraising machine powered by bikes. It is a community on wheels.

What do you need when you get bitten by a potentially rabid dog in rural Romania?

What do you need when you get nudged off the road by a van travelling at 50km/h?

What do you need when you get heat stroke and spend the night throwing up?

What do you need when you're feeling down and out, despondent and depressed?

What do you need when you're trying to raise £1,000 for charity?

What do you need when you get a puncture, fix a puncture, but can't get your tyre back on?

What do you need when you've run out of water and you're riding in 36 degree heat?

What do you need when faced with a 20km, 1000m climb, tougher and steeper than you've ever faced before?

What do you need when you make camp on a beach and the wind turns it into a sandstorm?

Yeah, that's right: you need community.

It's no secret that I believe in the transcendent power of long, arduous - even pointless - journeys. One night in a City members' club might raise half a fortune, but one week of cycling through Eastern Europe will spin your life around and give it a shove in an unpredictable, but always interesting direction.

Beyond the fundraising, the real outcome of such a week is immeasurable. What will become of the hours of thoughts, ambitions and secrets we shared? What will become of the muscles and friendships we built?

Shall we meet down the pub next week?

Or plan another long ride together?

And marry, before raising our kids on a farm?

Will I start a new job in pastoral care?

Or spend my days fixing bikes?

And my nights throwing fundraising soirées?

Will I spend the winter in Greece?

Or perhaps rural Romania?

And launch a rabies inoculation programme?

Cycling always creates plenty of space for upside down and inside out thoughts. Cycling in a community like Thighs of Steel adds camaraderie and caring, laughter and lectures, ideas, ideals, practical jokes, impractical jokes, cultures and creations.

My long journey back home is full of potential, and the promises and resolutions I make are easier to keep when I have a dozen new friends cheering me on.

Thighs of Steel is not just a bike ride, and it's not only a fundraiser. It's a community on wheels that, once built, can never be forgotten.

Huge thanks to everyone who has helped me raise £1,000 for refugees in Athens. I think it's time to get specific, don't you? So specific and heartfelt thanks to:

Jonny

Claire

Susan & Angus

Barrie & Maggie

Andrew

Tessa

John & Martine

Yvonne

Lee

Sabrina Edwards :D

And Anonymous :D

You're all part of an awesome team who have so far helped to raise over £77,000 through Thighs of Steel. That's an unbelievable amount of cash. THANK YOU.

For everyone else, it's never too late to join the team of awesomeness. Click here to donate!

This will be the last time I bang on about Thighs of Steel (in the newsletter at least), so if you've been meaning to donate but haven't quite got around to it, then please don't miss out. Every penny makes a difference to real people living difficult lives.

With one final push, we can beat last year's total of £100,000!

Thank you all once again.

I've published 527 Things on my blog. Here's one from the archives...

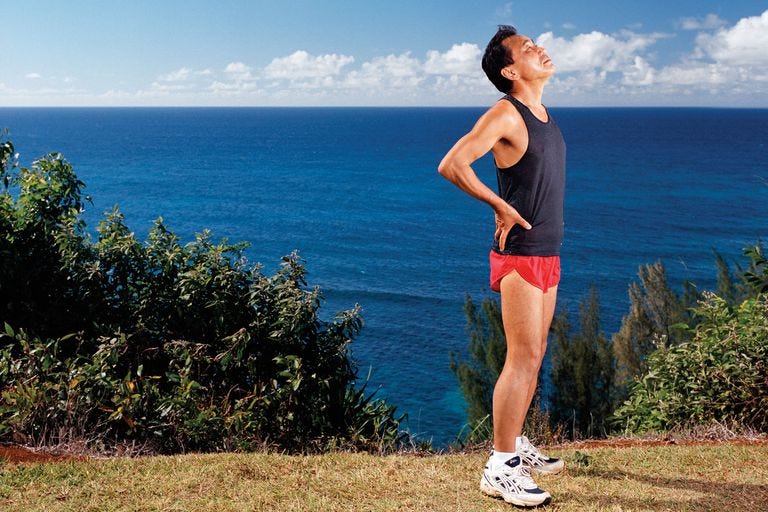

Murakami on Writing and Running

March 27, 2010

Murakami is a writer (and runner). That, according to the final pages of this book, is how he would like to be remembered on his tombstone. And, according to the vague thesis of this book, writing and long-distance running are not dissimilar. In fact, Murakami says that everything he knows about writing, he learnt from running.

So what was that?

Murakami identifies the three most important character traits for a novelist to possess:

Talent.

Focus. Murakami works for 3 or 4 hours in the morning. During this time he is totally focussed on his work-in-progress. He doesn’t think about anything else at all.

Endurance. A novelist needs the energy to focus every day for 6 months, a year or 2 years at a time.

Continue reading on davidcharles.info...

A Problem

I'm currently wrestling with how to put together a fundraising evening of readings and performances. Finding a suitable venue, asking people to perform, getting an audience excited enough to come out on a week night - all tasks that I haven't started addressing :)

>> INPUT

[VIDEO 5m] The Tim Traveller hikes the Speyside Way, a 105km-long National Trail in northeast Scotland. Dangerously, though, the path is littered with Tim-catnip: old abandoned railway stations...

[VIDEO 18m] Dave Evans at The Do Lectures. Dave Evans runs a programme at Stanford University that applies design principles to help people have a life that is both meaningful and fulfilling. The video is a riot.

[COURSE] The Science of Well-Being taught by Professor Laurie Santos on Coursera. One of the highest rated online university courses on the planet and I now know why. "The purpose of the course is to not only learn what psychological research says about what makes us happy but also to put those strategies into practice." Invaluable, even if you only watch or listen to half a dozen of the videos.

[NEWSLETTER] Documentally on Substack. One of the greatest newsletters of all time gets a subscriber-model makeover. Still plenty of free content, but twice the fun if you subscribe. Would suit fans of tech, interviews, boats, whittling and leaving bags on trains in warzones.

[FORAGING] Thistles are delicious, like a stick of celery or an artichoke. Who knew?

OUTPUT >>

Crossing the Border (August)

Thighs of Steel: Ljubljana to Sofia (August)

...COMING UP...

UK Ultimate Beach Nationals! Starts tomorrow and I'm terrified. How do you run on sand?!

A Thank You...

... to the interesting folks I met in the sauna yesterday. (Not as sleazy as it sounds...) An Iranian who works as a taxi driver, a Iyengar yogi, and a Pole who works in aerospace. Everyone's got a story!

Now On: The Victor Frankl 5-a-day Book Club!

Membership Criteria: Read 5 pages a day of Man's Search for Meaning to complete the whole darn text in only 28 days. I'll be tootling through the text at just 5 pages a week, so you've got plenty of time to catch up online.

Day 19

Today's excerpt is a little shorter (p96-100), as we reach the end of Part 1 of Man's Search for Meaning. These are the final pages of Frankl's description of the psychology of the concentration camp inmate.

Even after liberation, the former-prisoner is not out of psychological danger. For Frankl, progress from inmate to human being seems to have been slow and steady.

But for others, liberation was not so easy. Frankl describes the sudden release of mental pressure that occurred at the end of their imprisonment as similar to the bends.

Just as the physical health of the caisson worker would be endangered if he left his diver's chamber suddenly [...], so the man who has suddenly been liberated from mental pressure can suffer damage to his moral and spiritual health.

One class of former prisoner was susceptible to the influence of the camp's brutality: 'they thought they could use their freedom licentiously and ruthlessly'. Frankl describes one ex-inmate who wantonly destroyed crops, and another who threatened violent revenge.

Only slowly could these men be guided back to the commonplace truth that no one has the right to do wrong, not even if wrong has been done to them.

But aside from this 'moral deformity', Frankl identifies two all too common negative psychological responses of a return to free life: bitterness and disillusionment.

Bitterness grew when the former prisoner encountered the 'superficiality and lack of feeling' in friends and acquaintances who had not experienced imprisonment. It leaves the sufferer wondering 'why he had gone through all he had'.

Disillusionment was different: caused not by the apathy of one's fellow man, but by the feeling that fate itself was too cruel.

Looking forward to something in the future was crucial for sustaining hope during the war, but what happened when that long-dreamed-of future was dashed?

A man who for years had thought he had reached the absolute limit of all possible suffering now found that suffering has no limits, and that he could suffer still more, and still more intensely.

Disillusionment was the result of one's cherished dreams meeting the cold, hard facts of reality. Men whose wives and families were already dead suffered badly. As Frankl writes, 'We were not hoping for happiness ... And yet we were not prepared for unhappiness.'

Frankl ends Part 1 somewhat more optimistically: for every one of the liberated prisoners, the passage of time eventually covers over the horrifying reality of the camp.

As the day of his liberation eventually came, when everything seemed to him like a dream, so also the day comes when all his camp experiences seem to him nothing but a nightmare. ... [A]fter all he has suffered, there is nothing he need fear any more - except his God.

---

We continue next week...

If you enjoy what you read in this newsletter, you could do me a massive favour by sharing it on your networks. [Here's an easy, self-aggrandising link for you to Tweet] I'd love to write to more people!

(And if you don't enjoy what you read in this newsletter, I'd love to know why not!)

Much love,

- dc

CREDITS

David Charles wrote this. David is co-writer of BBC Radio sitcom Foiled, does copywriting for The Bike Project and is pretty much always available for work. davidcharles.info // @dcisbusy

Graffiti from 1719. Who was W.E.? What did they want to be remembered for?