#89: From Falafel to Slovenia

Happy Friday!

I left you last week on something of a cliff hanger. I was just about to make my first foray into Diavata refugee camp, a short drive northwest of Thessaloniki.

Since that first trip, I have returned Diavata another few times, and visited two other camps around Thessaloniki for good measure.

Our guide and translator was a Syrian engineer I'll call Abu Falafel. The first time I met him was at the house he'd been allocated by the ministry on the outer ring of Thessaloniki. It was on the ground floor of a unspectacular apartment building and he shared it with his youngest son, who is deaf.

Abu Falafel started, as all Syrians do, by ignoring our protestations that a second lunch would be unnecessary. He'd gone to so much trouble already, prepping ingredients, that we gladly acquiesced.

And so began the theatre of falafel that would give him his name.

Together we made not just falafel, those sizzling nuggets of protein, but also mutabbel, an aubergine foodstuff of a category that in English goes by the insufficient nomenclature of 'dip'. We need new words: meze is better. Hummus, babaghanoush, mutabbel, muhammara - these deserve better than 'dip'. They are the foundation of a meal, a far cry from the sauces that we use to flavour crisps, should we be so inclined.

Anyway, I digress heinously.

Abu Falafel, having filled the table with so many dishes that we had trouble squeezing ourselves in, defrosted sheaves of Syrian bread carted all the way from Athens. There are no bakers nearby that Abu Falafel can trust with the food Egyptians at least call 'aysh - life.

We eat Arab style, from communal plates in the middle of the table, scooping up falafel, mutabbel and hummus with torn bread. One of our number remarks that it's very different from the Western European style of demarcation and defence. My plate is my castle and, once I have been served, woe betide any diner who dips into my dinner.

Another reports a rumour that in certain high class German restaurants, guests will be requested never to return if they are seen sharing their food with their companions.

Abu Falafel tells us that everyone in Syria eats like this. Lunch at the oil company where he used to work was a sociable affair. Perhaps each might have their own bowl of fuul, if that was the dish, the sloppy nature of the beans making it somewhat difficult to convey in safety while reaching over a table - but in the main, there were a string of dishes in the centre and one shared equally with one's friends and enemies.

The conversation reminded me of a Frenchman I met in Athens. He'd complained that, while he didn't miss much about France, the one thing he did miss here was a convivial lunch. In Greece, he said, all his colleagues grabbed something on the go - here he paused to sneer at what passed for cuisine - and harried back to their desks to eat there, grateful to have a job at all.

It left no time for the small talk that builds friendships, he said.

Sharing food requires at the very least negotiation and a sense of equality. There's not much room for greed on a shared table. Maybe that's why we've drifted away from those habits in Western Europe.

But I digress obnoxiously.

When Abu Falafel had filled us to the point where doing anything other than lying supine for an hour would be medically irresponsible, we left the house for Diavata camp... And you can read the rest of that story on my blog.

Tomorrow I meet up with the Thighs of Steel gang and on Sunday we start our cycle to Sofia in Bulgaria. So begins two weeks of ridiculously ambitious cycling, including about 6000m of elevation and about 130km a day. If you haven't already, now's the time to join us in supporting Khora with bear coin. Donors will be spared a whiff of my cycling shorts. The rest of you - I can't guarantee what you might find under your pillow one day ;)

Teddies stitched by some volunteers in the USA for Carry the Future. Very popular in the camp!

>> INPUT

Buddhists in love by Lisa Feldman Barrett (Aeon). Big fan of hers. She's written an essay about love. Lovers crave intensity, Buddhists say craving causes suffering. Is it possible to be deeply in love yet truly detached?

Asylum Seekers Become Shepherds in the Yorkshire Dales for a Day (Positive News)

Reply All in vast quantities. Particularly good episodes include: Shine on You Crazy Goldman (microdosing), The QAnon Code (conspiracy) and The Return of the Russian Passenger (cyber security).

10 of the best words in the world (that don't translate into English) (The Guardian). A timely article, after learning that your vocabulary really can change the way you experience the world.

Five Things We Need to Know About Technological Change (Kottke) 4. Technological change is not additive; it is ecological. The consequences of technological change are always vast, often unpredictable and largely irreversible.

OUTPUT >>

Diavata Camp, Thessaloniki (August)

How travel works on the mind (August)

From Chios to Crisis (July)

...COMING UP...

THIGHS OF STEEEEEEEL! I'll be cycling from Sunday to Friday, from Ljubljana to Timisoara in Romania. So fingers crossed I'll be writing from there this time next week.

Everything's Puzzles, Episode 2 of Foiled, 18:30BST on Monday. This one's only got Miles Jupp all over it. Can't WAIT.

Catch up on Episode 1 here

Catch Episode 2 on Monday 18:30 BST on BBC iPlayer Radio

Now On: The Victor Frankl 5-a-day Book Club!

Membership Criteria: Read 5 pages a day of Man's Search for Meaning to complete the whole darn text in only 28 days. I'll be tootling through the text at just 5 pages a week, so you've got plenty of time to catch up.

Day 15

In today's pages (p78-83), Victor Frankl addresses the dangers of the past, the sufferings of the present and the promise of the future.

For concentration camp prisoners, the 'most depressing influence' on their psychology was the fact that no one knew how long they would remain imprisoned for. This created, in the words of one unnamed research psychologist, a 'provisional existence', to which Frankl adds 'of unknown limit'.

Most prisoners came to the camp knowing nothing of the conditions under which they would live. Once they arrived, that uncertainty of existence switched to when they would be released.

With the end of uncertainty there came the uncertainty of the end.

This uncertainty of limit made it very hard to for prisoners to live a purposeful life. The situation is comparable to that faced by an unemployed worker, who also lives a provisional life.

A man who could not see the end of his 'provisional existence' was not able to aim at an ultimate goal in life.

The hardship of the present and the lack of a future meant that many prisoners found refuge in the past. Although perhaps comforting, this retrospective rumination was, according to Frankl, somewhat dangerous.

Instead of taking the camp's difficulties as a test of their inner strength, they did not take their life seriously and despised it as something of no consequence. They preferred to close their eyes and to live in the past. Life for such people became meaningless. ... The prisoner who had lost faith in the future - his future - was doomed.

Such a loss of faith usually happened suddenly, 'in the form of a crisis', with familiar symptoms. The victim simply gave up on life.

Usually it began with the prisoner refusing one morning to get dressed and wash ... No entreaties, no blows, no threats had any effect. He just lay there, hardly moving. ... He simply gave up. There he remained, lying in his own excreta, and nothing bothered him any more.

Frankl himself would force his thoughts to turn to his future, for example imagining himself giving a lecture to a full audience on the psychology of the concentration camp. He quotes Spinoza:

Emotion, which is suffering, ceases to be suffering as soon as we form a clear and precise picture of it.

---

We continue next week...

Much love,

- dc

CREDITS

David Charles wrote this. David is currently gallivanting around Europe and will be talking to refugees in Greece. He is also co-writer of BBC Radio sitcom Foiled, does copywriting for The Bike Project and is almost always available for work. davidcharles.info // @dcisbusy

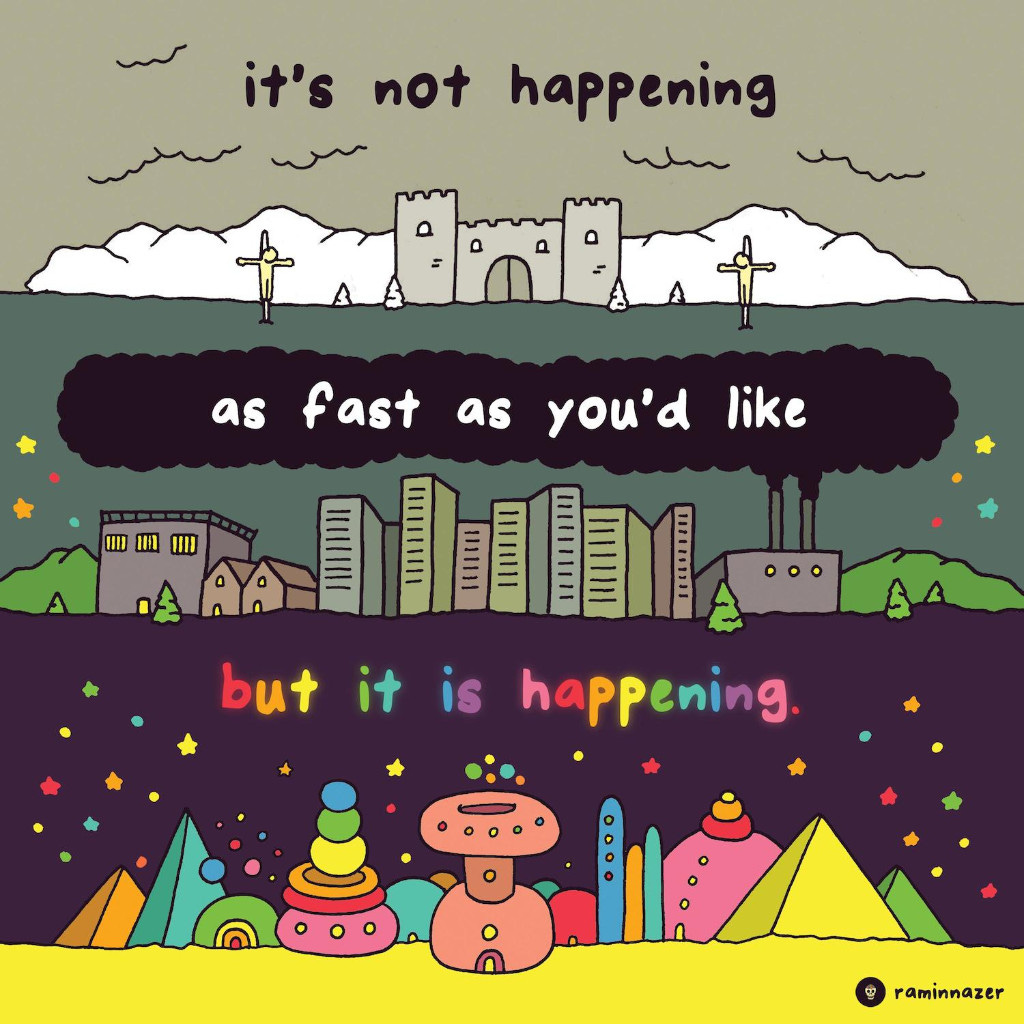

Comic by Ramin Nazer.